During the latest nights and longest weekends of 1993, id Software's developers shrugged off fatigue. Junk food energized the id team's bodies, but their shared passion for how Doom was shaping up invigorated their minds and spirits.

John Romero was especially excited. Doom would be the greatest game ever, and the 27 levels he and the team would be storing on floppy disks and sealing inside the game's lurid-red box were just the beginning. "What we did was, probably two weeks after the game, we released the level specs—sector def and line def information—so people knew what it meant and how the map files were created," Romero said.

The only thing Romero loved more than playing Doom was playing levels someone else on the team had made. Thanks to id's foresight, he would soon be swimming in an endless supply of space stations, spawning vats, and hellholes. There was just one thing missing: a level editor. Romero had co-authored DoomEd for id's level designers, but the program conformed to routines and processes specific to NeXTSTEP computers.

Along with level specs, id released a free node builder that players could use to design modifications, or mods. Doom's engine organizes levels in a tree made up of nodes and sub nodes, and every node corresponds to data for individual areas in a level. All summed up, nodes define a level's structure; the node builder would be able to render the nodes in a specific order to turn out a playable map, like a game of connect-the-dots that only turns out correctly if all the dots are in the right places and filled out in sequence.

"I knew that people would be wanting to make levels, which is why we put all that info out there. I knew they would have to write their own [editor]," Romero continued.

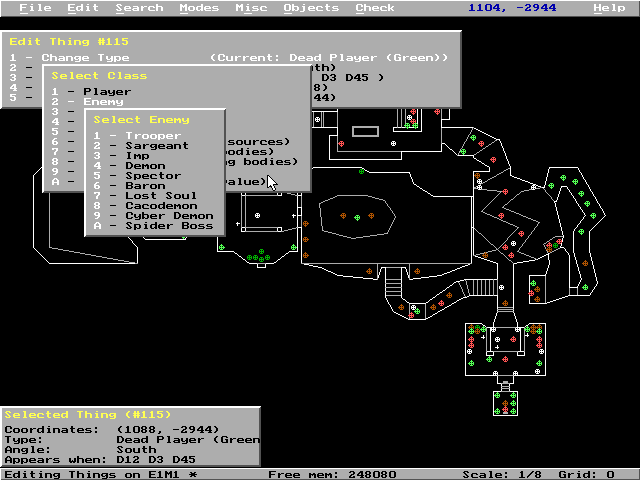

DEU (Doom Editing Utilities), one of the oldest Doom editors in extant.

Id Software's gift of free data, tools, and source code comprises the gift that keeps on giving to the Doom community. Innumerable level designers have harnessed that information to make Romero's dream of dreams come true: Twenty-three years and counting since Doom's release in December 1993, new maps sprout up daily. Some creators bend or even break id's rules to create something wholly original and far outside what the developers ever expected to see from their tech. Some color inside the lines—to be creative, to flex their level-making muscles, or to show that there's still plenty of gas left in Doom's tank.

Still other designers earned money and launched careers thanks to id's forward-thinking generosity. While browsing newsgroups late one night, Romero learned that a team of modders had been collaborating on a 32-level campaign for Doom 2—known as a total conversion, or TC—called TNT Evilution. The news post he had found was an announcement: Team TNT, as they were known, would publish their TC the very next day as a free download.

"One thing I thought should be happening was people making money from the amount of work they had put into making mods and levels and stuff," Romero said. "When everyone's putting free levels out there on the 'net, no one's going to pay for [content] from some unknown team. Who knows if [publishers] would want to publish that stuff. We found out later that people would do that, but at the time I just saw it and was like, 'These guys need to make some money from this.'"

Romero emailed Ty Halderman, Team TNT's lead designer, and asked if there was any way he could put the brakes on the TC's release. In exchange, Romero gave his word that he could help Halderman and his team see their work on store shelves. "He was like, oh my god! He contacted everybody; it was around 30 level designers. There were all sorts of political things going on because they'd wanted to release it for free, but [the creators] were like, 'But id would publish it. We'd get our name on an id title.' They all decided that, yes, they do want to see their game in stores and be part of the id series of released titles. They did stop the release of it, and we got everybody else signed up."

Around the same time, Romero discovered another team of modders, Dario and Milo Casali. The brothers were working on a TC called The Plutonia Experiment, another 32-level campaign. Romero saw an even bigger opportunity. He packaged TNT Evilution and Plutonia together, and id's publisher at the time branded the total package Final Doom and sold it as a standalone game.

"I thought that there were a lot of new ideas that we never would have made on our own," Romero explained. "It was ideas that people were doing out in the level-design scene anyway, and some new stuff. These people had released other mods out there before. There was a lot of stuff out there, and these guys paid attention to it and were very good.

Team TNT and the Casali brothers achieved fame throughout the Doom community, but they are only some out of a worldwide community of Doom modders whose work has been venerated by peers. Viggles, Scwiba, and Skillsaw—who preferred to be called by their online handles—are three of those who, like Romero, Halderman, and countless others who take pleasure in bringing their wildest ideas to life in the form of nodes, sectors, and line definitions.

Brigandine

Download link: Doomworld

When Viggles was 13 years old, a friend from school got hold of an alpha version of Doom and invited him over to play. The feeling he experienced was new to him within the context of video games. His hobby had made him excited, jubilant, curious. Doom was different. Doom terrified him.

"I was a huge Wolfenstein 3D fan, but that alpha scared the shit out of me," he said. "It was dark and suffocating and the physical rules of the world felt so different compared to the comforting Nazified grid of Wolf3D. I found it deeply unnerving, even though—or perhaps because—none of the levels were finished and the monsters didn't even move; some piece of that disquiet lodged in my young skull and never left."

Brigandine, by Viggles.

Viggles embraced his fear when id Software released Doom in 1993. For three solid years, it was all he played. His Doomguy marine did not venture forth into hell alone. "My dad strung a null modem cable from one bedroom to another for two-player deathmatches, which made me briefly the most popular guy in school."

Deathmatch was fun, but Viggles favored the game's three single-player campaigns. There was something unsettling—first deeply, then pleasantly—about moving through futuristic moon bases and demon-filled lairs. The abstraction with which id's designers had constructed the game's maps cast its charm over his mind like a web.

"Nothing in Doom is quite recognizable as a functional place," Viggles explained, "and that's vital to its aesthetic in some way. Attempting to make Doom look like real places collapses some tension in it and makes those environments much less interesting. As an adult I can perceive the practical gameplay considerations and the sometimes slapdash aesthetic impulses that went into Doom's level design; but when I was a kid it felt like those spaces had designed themselves, and that reading of the game I find unsettling as hell."

By the time he was 14, Viggles had tinkered with early editors like DEU (Doom Editing Utility). At that stage he had no ambition toward architecting master classes in level design. He was just inquisitive, driven to understand the black magic that so deftly delighted and unnerved him.

"The very first thing I made was a beach, with terraced layers of pebbles and sand leading down to water, and I was dismayed by how crappy it looked compared to the vision I had seen in my head."

As his aptitude grew, he plumbed deeper, experimenting with volume and perspective, lighting, and positive and negative space. No longer content to merely dabble, he became the archetypal sorcerer's apprentice. "The act of bringing my own spaces into being was almost intoxicating. When I was 16, I released a set of deathmatch levels themed around classical Greek architecture. They were dreadful to play because they weren't about gameplay at all; they were about me figuring out how to express ideas spatially."

Brigandine, by Viggles.

Viggles set Doom editors aside as new games arrived. He moved on to Thief: The Dark Project, and Quake, id's spiritual follow-up to Doom that sported real-time 3D graphics at blistering speeds. As games grew more sophisticated, his interest waned. More advanced games demanded that he learn more complicated tools. Designing levels was a hobby, a creative outlet that let him execute on a space he'd conjured in his head. Complex tools turned his hobby into a time sink, and he walked away.

Years later, Viggles found himself presented with an opportunity to rekindle his first passion. "In 2014 a friend of mine started making a Doom level on a lark, and I realized that I had been thinking about the Doom engine all that time: thinking about the ways it could be pushed, what it was possible to express in it, what kinds of (mis)treatment the textures lent themselves to. I still had visual ideas that had been sitting in me for 20 years waiting to come out, so I picked it back up again."

Returning to level design prompted Viggles to compare and contrast his styles from then and now. "Nowadays my design style is probably a response to contemporary games and how they feel," he said. "I guess I'm trying to make something that's unmistakably modern, yet that captures what I loved about how Doom looked and felt as a kid, which is why I restrict myself to the original textures and scripting features. Then as now, I find I'm still preoccupied with how a space feels, rather than how a space plays. I'm not very good at designing with gameplay in mind."

His first mod in years was Breach, a rambling tech base-style map. Once it was finished, Viggles conceived of Brigandine, his most recent map as of this writing, as a palette cleanser. He'd had his fill of space stations and wanted to build an environment that channeled the spirit of Doom 2's cityscapes—particularly that found in Map 14: Inmost Dens, built by former id designer American McGee.

"To get even more specific," he explained, "I wanted to give my due to a window texture that had a special place in my heart: BRWINDOW, which had been the only texture asset in Doom 2 to suggest to the teenage me that a Doom level could actually be a real place on Earth. It was also a way to explore some spatial ideas that Skyrim had planted in me; the starting chamber of Brigandine was originally a sketch of the temple of Kynareth in Whiterun."

Labyrinthine and daunting at first glance, Brigandine is tightly made—a compact space that loops in on itself multiple times, forcing players to pay attention to lest they become turned around.

"I'd originally meant it to work as both a single-player map and a deathmatch level," said Viggles, "so I studied a bunch of deathmatch maps to figure out their design principles. I made areas feed back into each other, so that players would come to new vantage points on places they'd been through before. The player ends up fighting several distinct battles in each area of the map as they come back upon those areas again."

Once he had Brigandine's deathmatch flow nailed down, Viggles sketched out a route for solo players. Like breadcrumbs, players would encounter enemies, key cards, ambushes, and items in a progression that took advantage of the map's interconnectedness. Ultimately, he said, the level flowed better as a single-player venture. "In the end the level grew too large to be suitable as a deathmatch map, but I think you can still see traces of it in the final layout."

Orchestrating Brigandine's progression induced its fair share of headaches, most of which stemmed from plotting out skirmishes. "Despite planning the flow of the level early on, and designing a bunch of the encounters in my head, I had sunk my teeth into the architecture way too early and fully detailed the areas before I properly playtested them with monsters," he explained. "This made for a painful process of figuring out what kinds of encounters each area could still accommodate."

Early in its construction, Brigandine's tight proves both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, its flow stands as one of the level's most intricate and compelling features. On the other, Viggles had little wiggle room to make even the smallest adjustments. Moving one piece would disrupt another, causing a domino-like effect.

"However, I had made those same mistakes already in Breach and learned some hard lessons from them. By Brigandine I had learned to leave enough room for my bad habits. As a result, most of the encounters I'd originally had in mind still made it into the level."

Viggles takes it as a point of pride that Brigandine conforms to Doom 2's original level specs... sort of. The game, known by the community as "vanilla Doom 2," sets hard limits that prevent players from flooding a map with more details than a level editor can handle. For instance, Doom 2 dictates that players can see a maximum of 256 wall segments. Though they might not be able to make them out, editing tools are aware of them, and planting even one more would cause glitches in the vanilla game.

"When id open-sourced the Doom engine," Viggles said, "the first thing that modders did was lift those limits into the stratosphere. Designers were still bound by the hard constraints of the original engine—walls can't move, floors and ceilings are flat, rooms over other rooms aren't possible—so it's still a challenge to fit your spatial ideas into, but you no longer have to limit the amount of detail you can have in view, which is very liberating."

Engines like Eternity and ZDoom are known as source ports, engines that embellish the capabilities of vanilla Doom and Doom 2. Contemporary engines allow for contemporary features such as sloped ceilings and floors, rotating walls, and platforms stacked directly overtop one another.

Viggles built Brigandine as limit-removing map—a modern level derived from vanilla features, but chockfull of significantly more of them. In other words, though Brigandine looks as though it could run in the original engine, players will still need a source port to play it. "I like the challenge of working within the feature set—and texture palette—of the original game," he explained. "I just don't care to carefully watch my sightlines, or to sacrifice cool architecture on the altar of not crashing a DOS executable that nobody ever plays Doom in anymore."

Brigandine, by Viggles.

As an example, Brigandine's staggering amount of detail and sightlines—line of sight for monsters—poke holes in Doom 2's parameters. "There are more lines in Brigandine than there were in the entirety of the original Doom 2, and any view from practically any spot in the map would crash the original game," he said. "That's not a laudable accomplishment though; most limit-removing maps could claim the same. Breaking the original game wasn't something I aimed for, it was just a consequence of the spatial ideas I wanted to express."

For Viggles, part of expressing Brigandine's space to its fullest involved performing tricks that exploit the original engine, such as a walkway that players can walk over and under. Viggles pulled that off by creating an invisible platform near the walkway that moves up or down depending on the entrance players come in from.

"Designers were using those same exploits 27 years ago, and though modern ports like ZDoom will let you do level-over-level stuff for real, I like sticking with the original tricks," he said.

Staying the course gave rise to a map Viggles is proud of. He's particularly taken with certain parts of Brigandine where players can look out and see more of the city in the distance—a level-design strategy employed in modern games that lean into interconnected design, such as FromSoftware's Dark Souls, as well as classic games, namely Doom and Doom 2.

"I love the visual suggestion that the player is in a much larger space that's just as detailed but that they can't quite get to," Viggles said of Brigandine. "This is one of the strengths of modern environmental design: older games simply couldn't afford to have it. These vistas took by far the longest to complete. I was still tinkering with them for several months after the playable space of the level was done."

Absolutely Killed

Download link: Doomworld

Were they to meet and swap stories of their Doom fandom, Scwiba could probably relate to Viggles' initial fright. He was only six when his older brothers installed Doom's shareware episode and proceeded to thrust him into a world of zombies and Imps and altars holding skulls and beating hearts.

Scwiba never forgot that fear. He hopes he never will. "I was too terrified to get past the first demons in the third map. I kind of feel like that deep-rooted childhood fear is part of the reason the game never completely left my consciousness. I came back in 2002 to conquer that fear, and never left. Why would you, when content for the game is endless?"

Scwiba has been looking for ways to tell stories all his life. He colored pictures as a tyke, wrote a small book in first grade, and, as he grew older, migrated to level creation. "I'm a storyteller and worldbuilder by nature," he said. "Modding and game development have always just seemed like another avenue for telling stories and building worlds. If a picture tells a thousand words, a video game level tells a million."

Absolutely Killed, by Scwiba.

Growing up, only games that included level editors slaked Scwiba's thirst for telling stories. He played as many as he could get his hands on, from WarCraft II and Age of Empires to The Incredible Machine and, his greatest pre-Doom obsession, Lode Runner: The Legend Returns. "I designed a whole lengthy campaign complete with a backstory and even a point where your buddy the blue runner heroically sacrifices himself and you have to go on to the final battle alone."

Scwiba dabbled in games on any platform, even putting out a ROM hack for a Final Fantasy game in 2000. He fashioned levels mostly for his own enjoyment until, in 2004, he cobbled together a Doom map called The Baron's Citadel. Writing off the effort as amateurish but instructive, he threw in with a group working on a map pack titled 1Monster in 2007.

"It was a community project where each map could only use one type of monster," recalled Scwiba, "so I suppose I was drawn to gimmicks and concept maps from the beginning. The biggest change in my maps over the years has been more confidence, if that makes sense. It doesn't have anything to do with style, but I like to think you can see it in the maps nonetheless."

Building up confidence impressed upon Scwiba the satisfaction he gleaned from extemporaneous design. His notions are like muses: one appears, and he allows it to lead him. Nearing the end of a project, he doubles back and varnishes spotty sections until they shine.

Absolutely Killed, by Scwiba.

As his confidence developed, so did his appetite for pushing the envelope of traditional map design. "That," he admitted, "and just having fun after what was a very draining and not fun development process on my last mod, Tower of Lies. Absolutely Killed was always pretty lighthearted and tongue-in-cheek—the name itself came from a line in a really nasty review of Tower—so my goal was just to dive in and treat the Doom engine like a playground."

Each of Ultimate Doom's episodes contain at least one through line. Episode 1: Knee-Deep in the Dead is set on military and industrial facilities on Phobos, and maps reflect that in their architecture. Absolutely Killed is analogous to a necklace of beads, each of a different shape, color, and material. "The unifying element is that they are all different," Scwiba said. "It's like a compilation of levels that would have been relegated to secret map slots in other projects."

Despite dissonance in one map's architecture and color palette to those of another, there is rhyme and reason to the order in which players tackle Absolutely Killed's levels. "'Barons of Fun' had to be first in order to ensure the player wouldn't have the weapons or ammo to actually fight the barons," Scwiba explained. "'Boxed In' is second so that it's early enough that getting a plasma gun feels like a big goal; it couldn't have been third because 'Call Apogee' needs to occupy that spot, the map slot with a secret exit."

The map order grows looser as players push deeper into the campaign. Scwiba's criteria for organization was to space out maps with similar gimmicks. "Hold the Hots" and "Pain" both incorporate damaging floors, and he didn't want to risk players growing bored or frustrated doing the same thing too often. "Breaking up heavier and lighter concept maps was a happy accident, but something I'll definitely pay more attention to in future projects," he added.

Like Viggles, Scwiba endeavored not to twist Doom's rule set, but to see what was possible within it. He took motivation from various official maps. "I suppose my process is to begin with a behavior I know of in the engine and then wonder—often off and on for months—how that could be used in new ways."

Absolutely Killed, by Scwiba.

One type of behavior found in Doom E1M8, the final (non-secret) map of the campaign, caught his eye. Players battle two Barons of Hell, and after killing the last one, the walls of the arena fall away to reveal an outdoor area. Scwiba played with tying environmental changes to the player's actions in UnAligned, the mod he designed after Absolutely Killed. "In the original map, that meant killing them opened the path to the exit," he said. "But could you make it into a bad thing? I know barrels block players from moving over them at any height, so they can be placed lower than the player and act as an invisible barrier. What does that accomplish that a regular wall wouldn't?"

Of all the novel concepts he toyed with, Scwiba feels that his design philosophies coalesced best in "Hold the Hots," the campaign's fourth level. "The concept ties into the visuals which tie into the action. There's a ton of Doom's traditional run-and-gun action, but the way it plays out is twisted and shaped by the gimmick of the lethal hellfire, and that gimmick wouldn't work without the distinct look of the red light spilling out into a gloomy dungeon."

Scwiba normally avoids slaving over one particular spot on a map, preferring to paint in broader strokes so that every step through a level provides a unique or challenging experience. However, "Hold the Hots" contains a few instances where he broke from his convention and lovingly constructed holes through which red light shines through like rays of sunlight, albeit with a hellish tint.

"That effect was much harder to achieve than you might think, so I'm pretty proud of it," he said. "I'm the most proud of making something outside of the community's norms and not stopping to worry about whether anyone would like it. I made Absolutely Killed completely for myself and had a blast doing it; the fact that it made waves at all is just a bonus."

Ancient Aliens

Download link: Doomworld

Skillsaw's introduction to Doom was far from terrifying. As a matter of fact, it was downright prosaic: He played the shareware, liked it, and bought and played through Doom and Doom 2. More than its frenetic gameplay, the game's community is what's kept him coming back.

"There are new releases on a daily basis," he said, "and the quality you can expect from each release seemingly gets higher every year. There's always something new to play and frequently by new faces that bring new ideas and perspectives. Doom manages to stay very fresh for a game that just celebrated its 23rd birthday."

Like many kids who grew up during the 1980s and '90s, Skillsaw played games often enough to feel inspired to make his own. Various editors for Doom gave him the chance to try his hand, although he admitted that his first efforts were far from memorable. "They were disorganized, very flat, and full of doors, mazes, and switches with no clearly discernible purpose."

Ancient Aliens, by Skillsaw and team.

One failing stood out more than others. Combat, one of the highlights of Doom, seemed incidental at best. "Which is fine, but nowadays, I like to mix in a lot of orchestrated scenarios in maps, and even include entire maps that are designed around a central planned gimmick that drives the gameplay," he explained. "I focus on flow and keeping the player on the right path, with some support for exploration and optional side areas here and there."

As much as he enjoys making levels, Skillsaw only brings an idea to fruition if it brings something unique to the table—a keystone that sets it apart from his past projects. "In Valiant I made heavy use of the gameplay modding features of my target engines to tweak the gameplay to support a projectile-spam style of play that I really enjoy. In Ancient Aliens I used a neon-themed palette and experimented in tongue-in-cheek storytelling. If I worked on a map set and it didn't have some kind of 'hook' like those, I don't think I would be satisfied with it."

Ancient Aliens has not just one hook, but several: dust-ups with extraterrestrials, a vibrant color scheme, and a custom soundtrack for starts. As is his custom, Skillsaw sketched out rough plans for themes, pondering textures to try out, and come up with a central hook—preferably something he hadn't done before—before breaking ground. "I usually have no idea what any of the maps are when I start them. As the map set fleshes itself out a bit, I begin to see what kind of maps I need to make to tie everything together and make those, but it's an organic process."

Ancient Aliens, by Skillsaw and team.

The campaign includes maps from over a dozen members of Doom's community, with Skillsaw wearing multiple hats to create palettes, build maps, and take point on level curation. "The initial hooks were I wanted to learn to edit the games palette," according to Skillsaw.

Combat, previously one of his weak spots, would play a more prominent role, although not a central one. "I wanted to make maps based around ammo starvation. There are some ammo starvation maps at the beginning, but I didn't stick with that theme long term so the palette ended up being the main driver. At some point I decided to explore storytelling in Doom a bit and worked in the tongue-planted-firmly-in-cheek conspiracy story and theme."

The first thing players will notice about Ancient Aliens is its beautiful color palette. A starry expanse enfolds maps. Transparent bridges edged with rainbow-colored borders connect roads lined with edifices painted in light purples, blues, greens, and reds. Cities composed of buildings crowned with arcane symbols spill out over expanses of clouds like a scene from a Star Wars film.

A meandering river surrounds a ziggurat in Map 18: Illuminati Revealed, built by Skillsaw himself. The ziggurat looks impressive from afar, but the detail is astounding when viewed up close—obsidian blocks laced with cerulean veins to resemble space-age circuit boards.

"I just wanted to make the wad look unique, and there aren't many wads that use the same color palette as synthwave album covers," Skillsaw said.

Skillsaw had no strict guidelines for who could contribute what for Ancient Aliens. There was but one central theme. "Movement is what makes Doom fun, so make sure movement feels good," he explained. "This leads to some soft rules about how open areas are better than tight areas, doors and corridors should be kept to a minimum, etc. But these are soft rules and sometimes going against them can make an area more interesting."

Ancient Aliens, by Skillsaw and team.

Rather than put out a call for designers on every Doom forum in extant, he stuck to places he frequented. Between 10 and 15 mappers volunteered, and seven committed to full maps. "Seeing what everyone came up with was awesome, especially because everyone brought their own perspective and their own ideas that I wouldn't ever have come up with, and the guest maps all stand out as highlights precisely because they serve as a break from my stuff."

Looking back on Ancient Aliens, Skillsaw found a lot to love in his own work, as well as that of his team. "The guest maps and the soundtrack composed by stewboy are fantastic," he said. "I'm extremely happy with the aesthetic and the style of gameplay in my maps; I think my personality and creativity are realized better in Ancient Aliens than in anything I've done previously. I'm not sure if the Doom community would agree or if they will remember it more fondly than anything else I've made, but that doesn't matter. I made it for me. The fact that other people were willing to contribute so much still blows my mind."

Still Fragging Strong

Designing maps for themselves has served Viggles, Scwiba, and Skillsaw well, but it doesn't hurt to know that other Doom fanatics appreciate and anticipate their work. Ancient Aliens and Absolutely Killed earned Cacowards from Doomworld in 2016, and Viggles published Brigandine in February 2017 to enthusiastic reception.

That transaction, creating levels for others to play and playing levels made by others, has resulted in an economy of maps that shows no signs of drying up. A big part of that has to do with the delicate balance between power and ease of use that Doom editors and other tools offer.

"Doom, when it first came out, was super huge," said Viggles. "Millions played it and tens of thousands made levels for it. It established itself as one of the first successful modding communities, and it was punk as fuck."

"It's a primitive enough game that one person's efforts in their free time can realistically result in the creation of something compelling," explained Skillsaw, "but it's complex and has just enough fidelity that the things you create can really be your own if you want to make the extra effort. Modern games are way too much effort to mod for in the way you can for Doom. There aren't a lot of custom campaigns coming out for new games because it's an impossible amount of work."

"You can draw a whole Doom map on a piece of graph paper since you don't have to worry about truly 3D space—unless you want to, in which case there are more advanced source ports," added Scwiba. "You don't have to know a thing about coding—unless you want to, in which case, source ports. That's the beauty of Doom: it's as simple as you need when you start, and as complicated as you want it to be once you start getting comfortable."

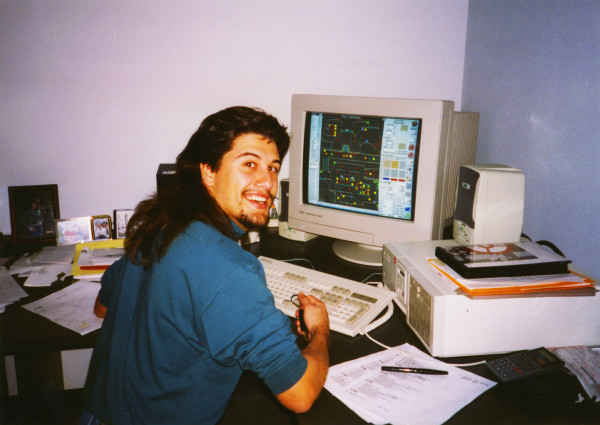

John Romero hard at work building maps for Doom. (Photo credit: John Romero.)

As for John Romero, he's glad to know he'll never run out of new levels to play.

"To me, Doom was almost like the analog to the Apple II, which lived far longer than it should have, being a computer from the '70s and living until the early '90s," he said. "Doom felt like analog to that computer, where it just lasted for so long and was just the perfect combination of simplicity and accessibility. It was easy to have fun with it in whichever way you have fun: it's easy to make levels, it's easy to deathmatch, it's easy just to pick up and play it, it's been supported for years. Source ports like ZDoom, Zandronum, and Skulltag, they're all really great. Releasing the source code was the best thing we ever did."