Jamie Gavin is one of the most Irish people you will meet. From his shock of red hair and thick beard to the fact that he lives along the blustery west coast of Ireland in Galway, he gives off scruffy artist vibes that would hang out at a pub till closing. Yet despite his local lad appearance, Gavin’s games are ones of deep existentialism set in a tech-fueled “post-truth dystopia".

Gavin describes his body of work as “a trilogy of five games.” These include three main games The Enigma Machine (2018), Mothered - A Role-Playing Horror Game (2021), and [Echostasis] (2024), along with “two standalone demos”, Mothered [Home] and [Echostasis] Prologue. Both of these demos work as previews of said games but also tell their own subversive stories if you dig deep enough and find their hidden content.

Source: Engima Studio

While his games deal with dark content, Gavin says, “I always try to promote horrific topics with a layer of empathy and care, so as to not be shocking for the sake of shocking.” He explains, “I feel like every one of the games I’ve made have always tried to have an underlying layer of hope.” While the games might broach upsetting ideas, Gavin thinks, “Ultimately the entire trilogy is a story about hope and continuing on in the face of trauma and identity crisis and all of these things.” Gavin feels that oftentimes modern games forget the importance of hope in good horror and storytelling, citing games like Bloober Team’s The Medium and The Last of Us Part II as games where, “the message seems to be that sometimes there isn’t any hope and sometimes it’s just darkness, and darkness, and darkness.”

When asked about where he finds his inspiration for stories like these, Gavin looks less to other art first and more to the real world. “It could be random things that happen to me or things [that I see in] human nature. [The] ways I see people acting and the various forms of bigotry that we might see nowadays and how the tech industries basically profit off of that and exacerbate it.” Gavin elaborates that these are, “Tech companies who are trying to replace each part of you with a new part that they own… [and] the ramifications of gradually, over the course of 10 years, selling yourself to a tech company, selling your data, all these things.”

Source: Engima Studio

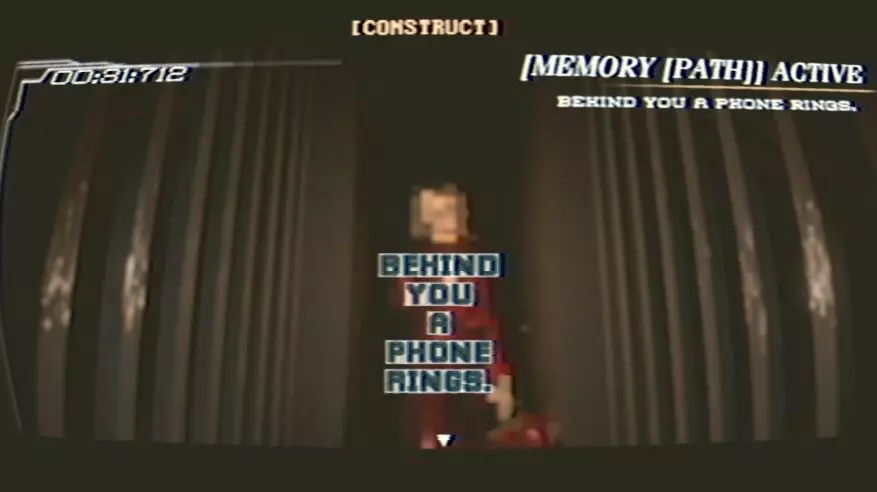

However, a key touchstone for Gavin does seem to be the Metal Gear Solid series - especially the stylings of the first game for the original PlayStation and the narrative subversion of the second game on the PS2. Gavin says, “I remember [that it was] the first game [that got] me to feel as though games aren’t toys anymore”, something he is also aware makes him sound like a teenager discovering Fight Club for the first time joking, “looking back on it now, it’s totally made for teenagers.” That said, the plot twist of Raiden being the main protagonist and the way MGS toys with being an interactive game has clearly spurred Gavin on. “A lot of the influence is very palpable in my work because it went very meta, and that was the first time I saw a game involve the player in the narrative.” Gavin says, “Since then literally every game [I have developed] has involved the player as a character in this world. Especially [Echostasis], where it plays through a whole narrative, the whole three-act structure, the credits roll, and then you realise, ‘Oh, I’m only a third of the way through this game.’”

Gavin seems fascinated in this exact moment, the moment when “all media literacy is lost, [and] you don’t know what part of the game you’re at.” He explains that toying with the conventions of storytelling lets you do much more interesting things with your stories. “The game ends and then it just keeps ending, and keeps ending, and keeps ending, [and] you don’t realise you have ten more hours left… [it’s] a really powerful thing”, Gavin says, “because then, once you can subvert all their expectations, [you can] start talking to them directly.”

Source: Engima Studio

All of this, paired with Gavin’s stories’ hopeful undercurrent can create some really impactful moments. “I feel like that is why players have resonated with it, [because] they feel like they’re being spoken to.” While [Echostasis] has its own narrative, Gavin made sure to still allow the player to be able to project their own struggles onto it. In the game, Gavin uses the words “What happened” constantly. “You need to face what happened,” or “You can’t change what happened.” Gavin explains that “each player is going to see what happened in a different light: It could be what happened in their past, something that they’re projecting onto their character, it could be anything like that.” As a result, Gavin says, “I am very careful about trying to see the player in this story, and respecting their intelligence as well as speaking to them in a way that I don’t think many other games do.”

When writing like this the stories of Gavin’s trilogy of five games feel much more heartfelt and much more real. So much so in fact that by time the Gavin is telling you the player, “no matter how bad things get there is always light at the end of the tunnel”, you might just believe him.

-

Lexi Luddy posted a new article, [Echostasis] developer Jamie Gavin on creating a horror trilogy over six years