Ahead of 'Bet on Black: How Microsoft and Xbox Changed Pop Culture,' our next Long Read scheduled for publication this Friday, Nov. 13, Shacknews is celebrating all things Xbox with articles and video features every day this week.

IN THE AGE OF 1995, two factions battled for dominance. WarCraft II's orcs and humans teamed up with Command & Conquer's Global Defense Initiative (GDI) and the Brotherhood of Nod to compete against the likes of Sid Meier's Civilization II for consumer dollars.

Outside the arena of consumerism, the two factions may have been friends. All that separated them was structure. To many, the Civ series represented the apotheosis of turn-based strategy gaming. Players could take their time thinking through every possible move, like a game of chess. The faster pace of real-time strategy games like WarCraft II and C&C drove the RTS subset of strategy games to significantly higher sales compared to turn-based games. Great satisfaction comes from coming up with a brilliant plan, being forced to scuttle it when enemies launch a surprise attack on your supply line, and turning the tide while your workers--those who survived the assault--hasten to repair your burning city.

Turn-based games hold tremendous merit, too. The average session of Civ II is likely to last longer than a game of WarCraft II, and being able to think several moves ahead and outwit your opponents is just as satisfying as pivoting in real-time.

As WarCraft II, Command & Conquer, and Civilization II continued to sell, a small group of business programmers asked the obvious question: Why not both?

Part 1: The Club

Like most siblings, Rick and Tony Goodman grew up close and went their separate ways as their adult lives took shape. A fortuitous series of events from their childhood caused ripple effects that reached years into their future.

RICK GOODMAN (design lead, Age of Empires): I was always into board games and I'd drag Tony into them. He was less into them than I was, but he was a worthy opponent. One of the very first board games I played that wasn't a typical board game was Avalon Hill's Blitzkrieg, a hex-based game about World War II. I was like, holy cow, this is a real game. There was armor, heavy bombers, medium bombers, a big board. I said, "I can do this," and failed miserably at copying it to create another WWII game. It's just a complex set of rules and takes years to master board-game-creation skills. As soon as I got into board games, I was modifying and creating my own board games. I could tell right away that the creative aspect was particularly intriguing to me, but I was never any good at it. The things I created in the board game space were just practice. I never showed any talent at it whatsoever.

Tony and I went to separate universities and on our separate paths. I went into accounting; he dropped out of college for various reasons. Then he started a consulting company and I joined that company. That's where it started for us. I was doing programming, and he was running the company. I was one of his employees. I played computer games like Civilization. Tony was less into gaming, but he enjoyed the culture and appreciated that game. One day, he walks into work, assembles the team of database programmers, and says, "Would any of you guys rather be making games than database applications?"

I think people were caught off-guard. We were looking around the room, like, "Is this a trick question?" But I raised my hand, and Angelo Laudon raised his. Tony was serious. He said, "I'm going to pull you guys aside and we'll make a game." I thought that was awesome. I said, "Okay! What kind of game?" None of us had any idea.

BRUCE SHELLEY (co-designer, Sid Meier's Railroad Tycoon, Sid Meier's Civilization, Age of Empires): I liked playing games as a kid. I looked forward to rainy days because I could do what I wanted to do: I read a lot, and I played games. I don't want you to get the idea I was a complete nerd. I was in Boy Scouts and played sports in high school and college. I played a lot of historic games, wargames. I subscribed to Strategy and Tactics magazine; it came with a game every couple of months. I started buying Avalon Hill games. I went away to college and we played a few games there. Not much, but we played Risk and Stratego with fraternity brothers.

I got out of college and I continued to play those games pretty much on my own. I met some people in northern Virginia who played, but the big breakthrough was going to college at UVA. They had a really good game club there. We met once a week and played a lot of different kinds of games. We even played roleplaying games. One of the guys in the club started a roleplaying game based on Lord of the Rings. We sort of formed our own game company out of that club called Iron Crown Enterprises. We wrote to the Tolkien family and got what we thought was permission to building roleplaying games based on Lord of the Rings.

We published rulebooks and adventures, and I was involved with that. I was doing some writing for them part-time; we were all working part-time. I went to trade shows for Iron Crown and met guys in the board game industry, and did some work for free for SSI in New York City, which published Strategy and Tactics magazine that I already subscribed to. I did some playtesting for them and research on their games for free. They had a job opening and I applied for it. They gave me the job, but the guy who hired me got fired before I started. The job turned into a three-month internship. I took it anyway. I lived in the Bronx with a fraternity brother and took the bus down to Manhattan. I developed a resume by helping to build a wargame for them, but the job went away.

I applied to other board game companies I knew: Avalon Hill and Games Workshop out in Illinois. Avalon Hill eventually wrote to me and had me come in for an interview, but they didn't write right away, so I went back to Charlottesville and took a job as a waiter. Avalon Hill offered me a job and I started there around January 1982. I worked there a little over six years, I guess. I liked the games and the people I worked with, but there was no money in it, really. They weren't paying much and I decided I couldn't do this for the rest of my life. Before I found something else to do, I found out MicroProse was based on the north side of the city, just in the suburbs. I wrote to them, and it took a year, but they finally had me in for an interview and they offered me a job the next day.

After a year or so there, Sid Meier asked me to be his number-two guy. I did all the things he didn't want to do. I was his playtester, his test manager, his writer, his sounding board, the guy who communicated with the sales team and managers and stuff. Anything he didn't want to do, I did; that was an incredibly rich experience for me and got me into computer games.

RICK GOODMAN: We sat in our office and did consulting during the day. Around five or six, we'd do game programming until nine, 10 o'clock. We had some long days because we were still billable, but we were willing to make the investment to make this transition happen, and it eventually did. Angelo is working with Tony and me now, and is just a brilliant programmer who can do anything. We didn't know that at the time, but in hindsight, he was the perfect guy in the right place when nobody knew what they were doing. He was the only reason we could do anything at all. He could carry any load we put on his shoulders.

I love programming. It makes me feel great. It makes me feel great to use a logical, analytical language to solve problems. I worked alongside Angelo for a year and realized he was three times faster than I was, and I would never be anywhere near his quality and expertise. I had to make a decision: This was not going to be a career I could do. He was just too good. I had to find something else to do. When his hand went up, I envisioned my role as being a designer rather than a programmer. Luckily for me, there was this opportunity.

By this time, Tony had hired a second engineer and one or two artists. Scott was on board; Brad was on board. We knew we had no idea what we were doing. I said, "You know, when I was 16 and you were 12, we went to the University of Virginia's board game club. That's where we met Bruce Shelley when he was a student. Now Bruce Shelley is a MicroProse-credit game designer. He's worked with Sid Meier. Maybe--maybe--he's not busy." [laughs]

BRUCE SHELLEY: We had a little conference inside MicroProse. They brought in teams that worked for us in other parts of the world, and people in the company gave presentations. Sid gave one on game design, and it was the first time I'd ever heard anybody discuss game design as a discipline. To me, it was really eye-opening. He made one comment that's stayed with me: "A game is a series of interesting decisions." I've been mulling that ever since. I've modified the definition a little bit and asked him within the last three or four years if that still held true for me. He said it does. I think it's not enough of a definition, but it's made me think quite a bit about what goes in when you're playing a game.

There were other things I'd learned but hadn't codified. One critical thing was prototype early and design by playing. I worked on board games where somebody had built games out of systems that were very cleverly designed, or so they thought. But no one had played it much until it was published. I thought it had a really small audience: The people who liked it, loved it; but the average person didn't get it. I thought, This is a mistake. Even working with Sid on Civilization, he and I were the only ones who played it for months. He didn't want anyone else playing it, so he and I played every day and talked about it, and he'd recode. I thought that was fun for me, but still a mistake.

What I took away from that was we still want to prototype early and play every day so we can make adjustments, but it's also important to have a lot of eyes on the product, people from all different skill types and interests. You have to break your games as you make them so someone doesn't break it after they're published.

I worked at MicroProse from '88 to '92. I got married and my wife was an executive at a large bank. She gave up a transfer and left the company so I could keep my job for a while, but she had trouble finding work in the Baltimore-Washington area. When she was offered a terrific job in Chicago, I left MicroProse. The Christmas party in 1992 was essentially my last day before we moved to the Chicago area. I was in the writing business for a while. I was a writer and wrote strategy guides for a couple of years for a publisher in California. They'd done strategy guides for games I'd worked on, and I asked if I could write some guides. They hired me and I wrote three, four, maybe five books.

RICK GOODMAN: Tony called him up and said, "Are you busy?" He said, "No. I'm not doing anything." He was just writing strategy guides, which wasn't stable. His wife knew he'd probably amount to nothing, so working with us, he could save face. [laughter] By the way, he has saved face.

BRUCE SHELLEY: Going back to that game club at the University of Virginia, the people who played on Friday nights weren't only undergrads, grad students, and faculty. Townspeople and children of people in town and faculty played, too. There were too brothers, Tony and Rick Goodman, whose father was on the faculty at UVA. I met them at the club. They were teenagers, and I taught them how to play Squad Leader, an Avalon Hill game.

I must have treated them with respect and made an impression on them. Tony said years later he remembered me playing a board game with a yellow pad next to it. As I played the game, I was taking notes on what I'd do to make it better. He was impressed by that. He hadn't considered that the game could be changed.

RICK GOODMAN: Tony's into games on a psychological level, but I didn't see him play a lot of games. He doesn't do the detailed design, but he likes the adventure of creating stuff. The first game I ever made was Age of Empires, and I had no experience. I was an accountant and a programmer. What I felt was, gosh, I have no idea what I'm doing.

BRUCE SHELLEY: Fast forward 15 years at least. Tony Goodman is in his 30s and has a business in Dallas. He's building software for banks and other companies, and he's got a lot of engineers working for him. They want to make games. They're gamers, so he calls me up out of the blue. He'd been following my career and wanted to know what it was like to make computer games: what was involved, what did it take. We'd have hour-long conversations about game development, and finally I told my wife, "I think he's going to start a game company."

Sure enough, he called me up and said, "I'm going to fund a game company out of my other company. My partners and I want you to be involved." I said, "Well, I can't move to Texas." He said, "You don't have to. You can work from home and come down occasionally." I went down and met them all, talked about it. That was the genesis of it. I was only a part-time employee for the first year or two. I think I'm officially employee number four. I remember somebody had a brochure showing I was the fourth.

RICK GOODMAN: So Bruce was on board, and it was him, myself, Tony, and Angelo.

Part 2: The Sun Was Shining

Real-time? Turn-based? The Goodman brothers spitballed with Bruce Shelley until they realized the idea that held the most potential was an amalgamate rather than a singular vision.

RICK GOODMAN: We talked for about six months about what the game could be. Bruce said, "Wouldn't it be great if we could do a train game?" Tony said, "Maybe we could do a puzzle game where you're on a desert island, and if you solve the puzzles, you get off." That was a terrible idea. The train game was an okay idea.

I thought about it and said, "You know, I like Civilization, but there are parts I don't like. The main part I don't like is that it's turn-based." I knew that was strange because I loved board games.

BRUCE SHELLEY: We had an idea for a game and we kicked it around for a while. One of the other early employees, Tim, came in with WarCraft one day and said, "You've gotta play this game. This is what we should be making."

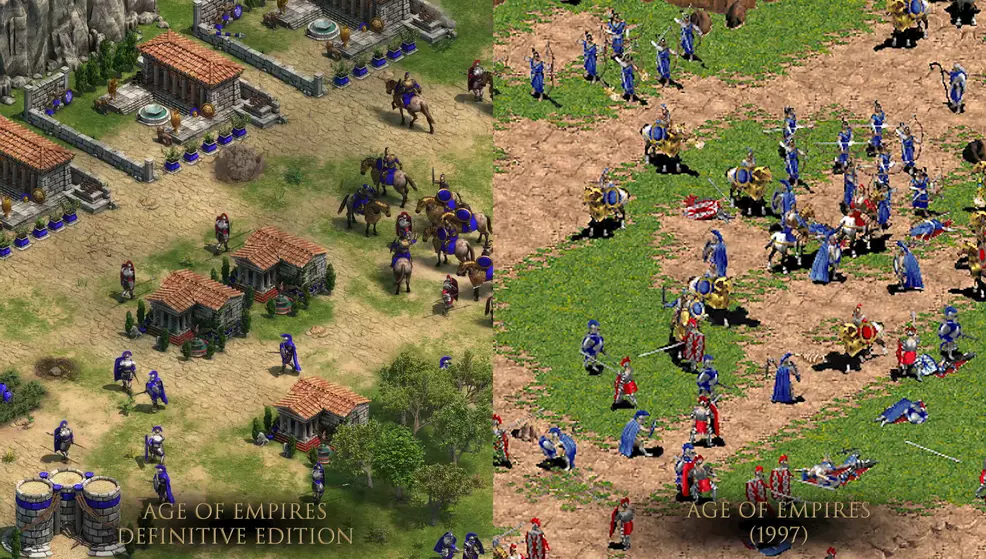

RICK GOODMAN: I'd played real-time strategy games. Dune II was out, and Microplay Software had put out a game called Command HQ. So I was pretty sure real-time strategy was fun in these early stages. During the development of Age, after we'd started, we saw Command & Conquer. A year later during development, that was about the time of WarCraft 1. Later, we saw WarCraft II. So during our development, we saw WarCraft 1, 2, and Command & Conquer. It didn't make us nervous, and I think that was probably because we didn't know what we were doing.

BRUCE SHELLEY: We played WarCraft and the idea came to us: We'd merge it with Civilization. The idea was to take the economy and races from civilization and merge it with the real-time gameplay of WarCraft and Command & Conquer. Dawn of Man was the first name we gave it.

Go back to the issue of a game being a series of interesting decisions. I think what really happens with real-time is decisions get a little more interesting because time is running. It's not a matter of sitting there for 10, 20, 30 minutes and picking out the optimal move, like in chess. Instead, it's important that you make the best decisions quickly. Time is of the essence because your opponent is making decisions, too. You don't have time to ponder. I thought a time limit made each decision a little more interesting.

RICK GOODMAN: What I saw was, hey, this is a pattern that we could copy. I wasn't pretending I knew anything. Bruce was the designer along with me, but he'd never designed a real-time game, so this wasn't an easy thing even with his experience. We just saw these patterns and said, "Okay, we understand this. Train units, move across the map."

BRUCE SHELLEY: We tried to get a prototype quickly. We played WarCraft every day until we got our own game playable in multiplayer. I remember I was in the office in Texas when we got it playable, and eight of us played at once. Maybe it was four. It was so exciting. We were cheering and everything as we played each other in our game. I believe that was the last time we played WarCraft. We played our game every day after that.

I gave a lot of my documents and stuff to the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York. A guy did a video where he unpacked one of my old CDs and started playing it, and it was something like the prototype we showed. It was a green world: green trees, grass. The sun was shining. We had basic units: horsemen, archers, swordsmen. We had a rock-breaks-scissors kind of setup where cavalry defeated archers, archers defeated swordsmen, and pikemen defeated cavalry. You wanted to mix up your units and attack the right stuff with the right things

RICK GOODMAN: We adopted patterns like the UI of WarCraft. We didn't pay as much attention to Command & Conquer because we felt there was a lack of sophistication, and that Blizzard had incorporated that, so that became more of our model. That had to do with unit behaviors and a better fog of war, which as gamers we felt created a more sophisticated playfield. That pattern was something we adopted.

BRUCE SHELLEY: I don't know if we had this at the time, but we added deer running around. So it looked like a real world that this conflict was taking place in. It was a little different, and I think what struck people right away was it had pretty realistic graphics. Tony goodman was effectively our art director at that point, and he got some really nice-looking graphics of these ancient characters. The sun was shining, which was different than these other games, and it was historic.

I really liked Civilization, a board game by a well-known designer from Great Britain named Francis Tresham. I did one of his railroad games at Avalon Hill called 1830. There's a whole genre of railroad games called 18XX, and I'm happy 1830 was considered one of the best in the whole series. So I was couched in history. I played all those historic wargames and I loved working on Railroad Tycoon and Civilization. Those games where I told my wife, "If I could make a living doing something else, I'd still do this all day for free." It turned out the lead designer, Rick Goodman, Tony's brother, and the other designer, Brian Sullivan, the three of us all liked history games. It was natural for us to do this Civilization-inspired game.

RICK GOODMAN: That was very instructive. Where I think we didn't have fear was we felt that the historical aspect was such a broad topic that it would appeal to lots of people. Those other games had science fiction and fantasy, but there was plenty of room for what we were doing.

BRUCE SHELLEY: Within a year or so of starting to talk about this product, I remember there was an article in a magazine--possibly Computer Gaming World--that said there were 50-some real-time strategy games in development around the world following the success of WarCraft and Command & Conquer. But we were the only ones based on a historic setting. Everything else was either science fiction or fantasy. I think that turned out to be a huge advantage: People looked at our game and got it right away, and lots of people are interested in history.

RICK GOODMAN: The original vision I had in my head was seven ages. You'd start in the Bronze Age, and that might take you farther toward the Middle Ages. What I realized during development was we had scoped out a product that was already big, and that may not be necessary to the vision. It was a whole lot of extra work on the design side, the tech trees and art side.

In the middle [of development], I scoped it back to four, which seemed like a really big cut at the time, but still felt shippable.

BRUCE SHELLEY: We thought the whole gamut of history was too much to encompass. We said, "Look, if we can make ancient history work, there are future periods we could move into with follow-up games." We were building a series in our mind, figuring out how it could work.

Part 3: Same, But Different

On the surface, WarCraft II and Command & Conquer seemed polar opposites. Just below their respective patinas of fantasy and futuristic warfare, they shared much in common. Orcs and Humans instead of armies in yellow or red uniforms. Two factions harvesting the same resources. Yet in 1995, that formula was proven. Ensemble's next mission was to figure out what to borrow from their contemporaries, what to reinvent, and what to create themselves.

RICK GOODMAN: I owe Blizzard a ton of credit. But at the same time, the challenge became, how do we differentiate ourselves?

BRUCE SHELLEY: We sat down one day at the office and on a whiteboard, we made a list: a column for Command & Conquer, a column for WarCraft, a third for Civilization. Each was a list of things we thought were great about those games. I don't remember the list now. Then we made a list of things those games weren't doing. The things they were doing really well became our minimum bar: We had to do those things as well as they were doing them, or at least most things. The list of things they weren't doing became opportunities: "This is how we differentiate our game." History was one thing.

RICK GOODMAN: Sure, our theme is different, but how does the game become its own game? What are we trying to do? It's easy to be influenced in a negative way and lose your vision. That was a struggle.

BRUCE SHELLEY: Years later, I gave a presentation at a DICE conference. The idea was somebody had to look at your game and say right away, "This is different. This is not something I've played before." One thing I remember was that in Command & Conquer and WarCraft, their AIs cheated. They didn't have a blank map like you did. They knew where you were, so they could come right at you. In our games, the AI doesn't know where you are. The AI plays with a hidden map and they have to search, just like you.

Another thing was WarCraft's maps were fixed. They were always the same. I wanted randomly generated maps. We'd had those in both Railroad Tycoon and Civilization, and I thought that was a powerful thing because the games were different every time you played. We had to work really hard to make the maps balanced so they could be used in competition, so one player wouldn't be screwed right away because of his end of the map. I remember a Blizzard player, Korean, who was really good at their games, and he told somebody at Blizzard: "If you move this thing one pixel to the right, I will never lose." We didn't want that. We wanted our game to be a different experience every time.

Figuring out differences was a good first step. Next, they had to put their growing game through its paces to determine whether the concept held water.

RICK GOODMAN: Never had I thought about how many civilizations there should be. That seemed tangential to, "How does this game work? Is it fun to play?" Maybe 18 months before the end, we had to deal with this issue of how many civilizations to include. We only had one pattern, the WarCraft and Command & Conquer pattern, where there are very few factions and they have some unique differences.

I thought that was neat, but because I read a lot about history, I realized that in our theme, there were a lot of historical civilizations that mattered, that left a mark on the planet--from the Venetians to the Greeks and Romans. Everybody knows those last two, but there were many, many more. I didn't feel comfortable with picking three, so we decided--and this was a risky move--that we would do six, eight, or nine. But we knew right away that would entail tremendous compromise in terms of art. People would be using the same art assets across different civilizations, which may not make sense. But we would have the ability to say, "How'd you like to play as the Babylonians this game and the Phoenicians next game?" I thought, There's no right or wrong answer. It's a leap we're going to take.

BRUCE SHELLEY: We definitely wanted to give the civilizations a different feel. They were different cultures and there were differences in this period between the Roman legions, the Greek phalanxes, the elephants from Persia, stuff like that. I remember playing games where you tried to recreate, "How did Alexander the Great with his tiny army beat this huge Persian army?"

I remember reading about the evolution of warfare in Strategy and Tactics, how one of our technologies was the stirrup. That changed warfare. Until the stirrup existed in the Middle Ages, horsemen were just hanging on for dear life. Once we had a stirrup, the whole horse became a weapon. The strength and weight of horse and rider concentrated at the point of the spear. When that hit somebody, it was devastating. Without that stirrup, it hurt, but it wasn't quite the blow that a mounted guy on a stirrup could deal.

RICK GOODMAN: Some people like to have the theme inform design. I'm the backwards kind. I ask, "What are the mechanics, tools, and hooks in this game that we can expose, manipulate, and fold into civilizations?" Looking at my library, I have almost all the books on those ages. Probably 50 of them. I tried to get print books that talked about each civilization. I'd read each one and found quite a number of cases where the historical attribute of a civilization was something we could work with. I was pleasantly surprised. That was maybe 40 percent, but in our case, we really only needed one grand theme for a civilization that was historical enough to make people believe. Like, they know Rome was good at X and the Greeks were good at Y.

We set up data so they were all unique to some degree. The risk was, are they different enough? Will you believe that your swordsman is different than my swordsman even though they look the same? We made the statistics different, but I didn't know the answer to that question because it hadn't been tested in a Blizzard or Westwood game. If you look at the scope of what you get to play with in the first two ages, there isn't a whole lot to work with. That becomes part of your tech tree, and it gave us more hooks: more items to work with later, more changes in the database later. That created more differentiation in terms of statistics and attributes.

BRUCE SHELLEY: The stirrup changed warfare for a couple hundred years, and then there was a response to that: Pikemen came along. Horsemen were now at risk. By the American Civil War, there wasn't much use for cavalry on a battlefield. That whole arrangement was important and a nightmare to balance. We didn't want everybody to only play one civilization. We wanted all the civilizations to be viable. That cost a lot of time playtesting and tweaking.

I've told people before that you should do your research in the children's section of a library. You want to reach out to a lot of people, not just the experts. I remember Age of Empires got a review in a history magazine that said, "The history here is really weak. There's not much going on." At the same time, we were introducing thousands and even millions of people to ancient history, so what's wrong with that? That's a positive thing. We did stuff like add the Hittites as a civilization. They're mentioned in the Bible and weren't even discovered as a civilization until some point in the 19th century. Now we know they were southeast Turkey and some northeast parts, too. But they were just names in the Bible until archaeologists identified them, so we had them in our game, and that was cool.

Part 4: Gathering Resources

Since Rick and Angelo tentatively raised their hands and joined Tony in his quest to make computer games, most of their work had been done off the cuff: think of X, try X, ride that momentum or come up with something better. Some talk of finding a publisher occurred, but nothing concrete was decided--until, suddenly, it was.

RICK GOODMAN: Nine months after we raised our hands, Tony said, "I've invited Microsoft to come see our demo." That came out of nowhere. I was like, "Uh. Okay. Why would they come visit us? We don't have a game and we've never made a game." He said, "No, they've agreed to come." This was really Tony's modus operandi: One weird thing after another that a more logical person like me would say, "That's a crazy idea. That will never happen."

BRUCE SHELLEY: Tony had met some people from Microsoft at a game show. He also met people from a publisher in Dallas, and people from Hasbro Interactive. A friend of mine who I'd met at MicroProse was working for Discovery Channel, and they were playing with the concept of making games. Two guys from MicroProse came to Dallas to look at another game by another company, and they asked if they could come by our office for an hour and take a look at what we were doing. We said, "Sure, absolutely." They ended up staying four hours. They said, "We want you to bring this game back to Redmond."

We did a road trip. We flew to Boston and showed the game to Hasbro, then flew to Redmond. By chance, one of Microsoft's executives, a fella named Stuart Moulder--we'd spent a day together at a TV station in California. He was showing products from Sierra On-Line; I was showing Railroad Tycoon for the Macintosh, I think, on a TV show called the Computer Chronicles. We spent the day together and got to know each other pretty well talking about the games industry. So when we showed up at Microsoft to show our game, Stuart and I already knew each other. I had worked on Civilization, and Stuart and the other guys there were gamers. That gave us a leg in the door.

STUART MOULDER (product manager, Microsoft Game Studios): Our charge was to bring street cred from the games industry. Tony Garcia and Ed Ventura came from the games industry; now I came from there. We were supposed to find and deliver games for gamers. We built the group up and it quickly grew and split into several smaller business units called product units. I was put in charge of one of those. My line of business was to go out and find action, adventure, and strategy games, "core" games for gamers. We had some hits and misses, but the big hit was Age of Empires with Ensemble Studios.

TONY GARCIA (general manager, Microsoft Game Studios): One of the guys who worked at a company where I'd worked had gone to Ensemble. He reached out and said, "You've gotta see this demo. It's really cool." They had an early demo of Age of Empires, and I fell in love instantly.

STUART MOULDER: I had a bunch of business development/talent scout people in my unit who went out to talk to game developers and try to find project. The idea to build a games business at Microsoft was not to develop games ourselves, but to find people who already were in that process. One of my biz guys, Ed Ventura, stumbled on Ensemble. He was very intrigued by what he saw. He said I should go down and take a look.

ED VENTURA (product manager, Microsoft Game Studios): Our introduction came from timing convenience. I was working on another title with Terminal Reality out in Plano, Texas. I had earlier received a game proposal from Tony Goodman. He didn't have an official game studio at the time, but was working with his brother, Rick Goodman, on a real-time strategy title. Tony invited me to take a look at a prototype they built should I be in Texas. Because we were looking for titles to fill our portfolio, I was looking for one that would fill gamer interest for another hit at the time, Total Annihilation by Chris Taylor.

Side note, Chris and I became friends, and Chris started building games for Microsoft in the future.

Back to Ensemble. My program manager, Robert (Bob) Gallup, and I were in launch mode which required us to stay longer in Texas. I was reviewing my other game proposals and suggested we stop by Ensemble after dinner one night. I reached out to Tony and we set up an appointment to meet. When we got to the office, Bob looked at me and said something like "Are we in the right place?" We had walked into an office that appeared to be a Microsoft vendor support business.

Tony came out to greet us in a business suit. And the other staff was dressed semi-formally as well. However, he directed us to a side room where we met Rick and a few other members not in suits sitting at a table. They were not part of the vendor support business Tony owned. Rick and Tony complemented each other very well at the time. Rick being very animated and extraverted. Tony was very articulate, cerebral and introverted.

Anyway, I remember Rick doing the pitch and the prototype really demonstrated their passion for history using a real-time strategy game engine. It was a working prototype which Bob looked at more closely from the technical view. Because the market was going up for real-time strategy games, I was very excited to bring this to Stuart, my boss at the time.

STUART MOULDER: Both Command & Conquer and WarCraft II had really good performance in terms of sales. At Microsoft, we were more fans of Command & Conquer. But the people at Ensemble were more WarCraft II fans. They wanted to make their own WarCraft II, but hybridized with aspects of Civilization.

RICK GOODMAN: Microsoft shows up, and what we had was an isometric grid in 2D that looked like a chess board. It was undecorated. In the middle of this grid was just squares with a palm tree. There was one man, a villager. He would go back and forth between a stone mine and the palm tree, picking up stone and dropping it off at the town center.

That was it. I was like, "This is not going to sell."

STUART MOULDER: When I sat down to play what they had, there was very little there. You could get a little campfire on the map and a little caveman. You could hunt food, gather it, and build some huts with the goal of getting to the second age. There wasn't combat yet. Just hunting and gathering, essentially. But something about even that activity was really engrossing. We all liked it immediately. We all felt like, "Yeah, we want to do this." We signed them up.

RICK GOODMAN: Microsoft picked it up. They said, "We want to move forward and do this game." I had no idea.

TONY GARCIA: It was one of the first in its genre, really. You had a bunch of forces that you selected, and you built them up, you created your fiefdoms from nothing. It was an amazing demo. We were sold the minute we saw it and signed them then and there. I said, "Let's do it. Tell us what the production budget is and let's go." That was a monster title. It led to a lot of other games like it. It was a game changer.

BRUCE SHELLEY: Microsoft was by far the most proactive about trying to pursue the idea of publishing this game. They were relatively new in the games space at the time and were looking for cool projects. They became our publisher.

STUART MOULDER: There were two secrets to that demo, I think. One was the look of it. Tony Goodman was not only running the company; he was also the art director. He directed them to create a beautiful world, a world you'd want to be in. It was very different from the dystopian, dark look that really dominated games in the '90s. Games like Doom and even WarCraft II, which is still a dark fantasy world, and Command & Conquer was set in a dystopian world. But here was a world that looked like our world. The things you did in the game were easy to understand because they were from our world. You hunted and gathered. You eventually built military units that made sense to you: guys on horses went fast, guys with swords moved slower but were sturdier guys with bows that shot arrows a long way.

The second was the game was intuitive and easy to grasp. They'd done a good job with the controls, mostly lifting from WarCraft II, but they'd found a way to seamlessly and interestingly grasp the more complicated technology-research aspect of the game so you could do more of that Civilization-type of thing. Even early on, the look of it and the gameplay base were engrossing.

RICK GOODMAN: During negotiations, Tony [Goodman] said, "Ask them for 600,000 extra dollars." I'm like, "Tony, they're not... they won't... you don't just ask for that." Then I did, and they did. Time and time again, he's doing crazy stuff, eventually teaching a person like me that a bit of foolishness is needed to achieve great things. I'm more the guy who comes in every day, punches the clock, and does heavy lifting.

Maybe it was a combination of the two that was helpful, but he definitely did things that made me tell him, "We're wasting our time." Like calling Bruce and going, "Hey, how'd you like to work for us?" Bruce hadn't seen us in 16 years. But that's how Tony was.

Ensemble's real-time-meets-Civilization game was one of countless projects at Microsoft. Although they had the games group's full support, they needed the backing of one person, the right producer who believed in them and their vision, to build their game from prototype to finished product.

RICK GOODMAN: We had a great producer who was super-collaborative. We loved him to death. Microsoft put the right man on the project.

TIM ZNAMENACEK (producer, Age of Empires): The first time I saw it was November or December of '95, somewhere in there. I remember this like it was yesterday. Age is the highlight of my career in gaming.

RICK GOODMAN: He was very passionate about it, but he wasn't pushy. He'd say, "That sounds fun," or "That sounds less fun." We really respect him to this day. He had full control but he was very collaborative. That helped a lot.

TIM ZNAMENACEK: I remember business development had gotten a pitch and some kind of demo. I think it was called Tribe at the time, or maybe that was the codename we gave it. Somebody grabbed me and said, "You've got to check out this game." I went to Tony Garcia's office and he was playing it, and I said, "Oh, this is so cool." I played WarCraft, Command & Conquer--I loved that type of game. I saw Age, and it was right up my alley. The animations, the setting--everything was super-cool. I got a copy of it, of course, and just played and played.

There was very little, if any, combat in [the demo]. It was just collecting resources. You could build buildings and stuff like that, but it was super, super-early. I bugged my boss continually until he let me be the producer of that project. Once a project got signed, you'd have conversations about which producer in the group would work on it. I was working on something else at the time, but I can't remember what. They said, "We don't want to put too many projects on you at once, Tim." I said, "I've gotta work on this one. I've got to."

STUART MOULDER: I remember Tim absolutely wanted that game. I think he saw--and a lot of us did--that this was our first shot at a really big, "gamer" game. He wanted to be the producer on it, and was 100 percent committed to championing that game.

With both parties excited about their future, Microsoft and Ensemble made their partnership official. Six years and two bestselling titles later, Microsoft Game Studios acquired the Age of Empires developer.

BRUCE SHELLEY: We had a good relationship, and the issue was the president of our company, Tony, and his partners wanted some certainty in their lives. Selling our company would be one way to do that. I wasn't part of the negotiations to that extent. I was with Tony when we asked them to buy us. He asked me to go with him, and the accountants got together and decided how this would work. I didn't even know the negotiations had gone far.

We were supposed to have an off-site meeting in California for the leadership of the company at a resort. We walked in the door, all these Microsoft people were there, and we were told, "Okay, the meeting's not going to be what you think. This is going to be a discussion about an acquisition." That was a big shock.

TIM ZNAMENACEK: We were the only ones who spent a large amount of time in QA iterating on bugs to release a really stable product. We helped with platform development, like if developers ran into issues with Windows. We developed marketing, all the user education materials, the print stuff you got in the box and the box itself--that was all developed at Microsoft. We also had each discipline that worked on a game offer feedback, help with techniques, all those kinds of collaborative processes from the publishing side.

Producers were essentially responsible for bringing the product to market. I didn't own business relationships, but I owned the day-to-day working relationship between Microsoft and Ensemble. I went there once a month for about five years throughout development of the Age of Empires games before they were acquired. I was very focused on it.

TONY GARCIA: We left them alone in their space. They built a title and did a great job. The Flight Simulator acquisition was different. It was our bread and butter, and we felt it necessary to have them close. That didn't make sense with any other company. Everybody sort of stayed independent. Access Software, Terminal Reality--I've always felt it was best, wherever possible, to let a studio's culture stay what it is so they can develop great stuff and let them do what they do best.

Part 5: Feedback

Microsoft's games group had grown from insignificant insect to slightly-more-significant insect thanks to Tony Garcia's belief in his talent scouts who'd hit on deals like Age of Empires. As the group's revenue increased, Garcia felt the walls closing in.

TONY GARCIA: We were off the radar making maybe 30 to 40 million bucks. Then we were making 80 million bucks. All of a sudden, they were taking us seriously. When that started to happen, people said, 'You know, we should get serious about this.' We'd been serious about it for a long time. Internally, other people were like, 'Eh, it's a games group. They're doing kinda cool stuff. It's all right.' Now, we were still a blip from a revenue perspective. But from a revenue and consumer perspective, we were becoming significant. Then you have a different cast of characters.

When that happened, they started to get a bunch of people who didn't know anything about games in management positions. I'm just not that kind of a person. I can do it, but I don't like doing it. Putting together a 50-slide PowerPoint with numbers crunched down to the Nth degree? That's not who I am, but that's who they thought they needed. They just needed a different person at that stage, I guess. That's fine. I have no regrets and really enjoyed my time there.

When people ask me about it, what surprised me most was Microsoft allowing this little maverick group to exist in the first place. We were against a backdrop of trying to learn the market, to control platforms, all that stuff. It was like, 'Wow, you're going to let us do this?' They did, and we had a great run.

Garcia departed during Age of Empires' development. His successor, Ed Fries formerly of the Excel and Word teams, made sure Ensemble's project never missed a beat.

ED FRIES (general manager of games group, Microsoft): Obviously Flight Simulator was a great product and had been around a long time, but it never got credit as being a game. Flight Simulator had a huge modding community. People would fly a jumbo jet in real-time across the country, like six hours or whatever. They were hardcore in their own niche, and maybe some people didn't consider them to be true gamers or whatever. Those fights go on to this day. But Age of Empires was really the turning point for us to start being recognized.

Honestly, it was seeing they were making an RTS that got me excited. When I was interviewing for the job, I didn't get to play it, I just got to see it. Age was under Stuart Moulder. Stuart had a great business guy named Ed Ventura; Ed worked really closely with Ensemble on milestone payments, the business relationship, things like that.

EDWARD VENTURA (product planner, Microsoft): We would morph our team on the Microsoft side to match what a developer needed. We were able to find resources a developer could never afford. In addition to funding salaries, we could provide help they didn't have. Things like artists, writers, all of those roles that are crucial.

No matter how big or small their project, all game developers believe in the power of iteration. Developers at Ensemble and Microsoft held frequent playtests--sometimes weekly, more often daily. Each test galvanized them to try new concepts and exposed flaws they needed to fix as release drew near.

RICK GOODMAN: The process was collaboration. I sometimes look back and name myself the coordinator. What worked for us eventually was two things. One was you look at time in development as a resource, like collecting wood. The more of it you have, the better off you are. We took a lot of time. A lot of time. Most companies would not have survived that length of time. It was a great resource. The other thing was in the collaboration, we got to playtesting.

TIM ZNAMENACEK: One thing Tony Goodman insisted on, which I thought was fantastic, was that everybody play the game. They set up a special place so everyone could be together and made sure the current build was on everyone's machine. All the designers would play different scenarios: "Let's play with this strategy" or "Let's play this civilization against that civilization."

RICK GOODMAN: Once we started playtesting rigorously every day, we collected a debrief. I folded that into our schedule. Before 6:00, I was a producer and a coordinator. From 6:00 to 10:00, I was the designer. I would take our debriefing into design and recommend changes for the coming weeks. It was pure iteration based on team feedback that slowly moved our game in a positive direction, but it was really slow. A year of daily playtests to get to where it was first playable to fun. It was a long, long time.

TIM ZNAMENACEK: Everybody on the team [on the Microsoft side] played it constantly. We had no shortage of people volunteering to play. It became our five o'clock, let's-play-something-for-fun game. During Age II, I had more than one manager in other departments email me and ask me when we were planning to do our beta. They wanted to know so they could understand the impact it would have on their development schedule. "Can you just tell me when you're going to do the beta so I know when my engineers will be distracted?"

RICK GOODMAN: One of the inherent advantages of our design, which was true of WarCraft and Command & Conquer, was you start with almost nothing. You never miss the full agency over what it is you're looking at in the endgame. If your endgame is massive and comprehensible, it's because you took steps to get there. There was another aspect that was, I think, the major thing we were most concerned about, which I didn't have a solution for.

All developers playtest their games. Microsoft went a step further by assigning experts from their usability research laboratory to every project. The researchers' forte was stepping outside the box of game-savvy analysis to find ways to communicate better design and mechanics to all types of players.

ED FRIES: Ensemble did an amazing job, but it was their first game. There was a lot of stuff they didn't know. Also, we were starting our user research department, so we did a ton of playtesting and gave them a ton of user feedback.

BILL FULTON (user testing lead, Microsoft): WarCraft was a beautiful game, and Age took that and added the component of historical growth. WarCraft games grow in the sense that your empire grows, but it didn't have that feeling of, now you're in the Bronze age. Technology wasn't as large a portion of it. To me, WarCraft felt performative: build fast, then take advantage by using your strengths against your opponent's weaknesses. Age had that, plus a great feel to it. It also had greater variety. The tech tree was bigger, so you had more ways of trying to win.

TIM ZNAMENACEK: Microsoft had this user testing discipline established, the equipment, special rooms with the two-way mirrors. We did a lot of testing and tuning for the tutorials, for instance; and the interface design: making sure goals were clear, things like that.

BILL FULTON: Trying to test it was interesting. I was familiar with the genre and the history aspect of it, but getting people who knew neither, and realizing, Wow, they don't know resources exist. They just think it's scenery. And Oh, you can hunt deer, but now they're trying to hunt birds, but you can't, because they are scenery. Certain fundamentals like that, they don't know there are resources. They don't know villagers aren't warriors.

All the knowledge you bring with you if you know the genre is problematic for helping you get someone who doesn't have any of that knowledge into the game. That's where the importance of the tutorial came in for games with the complexity of Age of Empires.

ED FRIES: We'd send them feedback of people playing the game and struggling: not knowing how an RTS works. It almost got to the point where we had to teach people how to use a mouse so they could play the game.

RICK GOODMAN: Accessibility wasn't the main topic, but it was pretty high on the list. That was our own sensibility, but also Microsoft's. I think we were all on the same page on what "accessibility" meant.

TIM ZNAMENACEK: Tony Goodman was really impressed by Blizzard and what they'd done. He saw the strategy space was booming, and he was pretty deliberate about using that genre model, but putting it into an accessible setting that was way broader than WarCraft. Blizzard may have outdone us in unit sales, but the variety of people who were attracted to Age of Empires was super-wide.

BRUCE SHELLEY: A friend I used to work with at Avalon Hill told me Age of Empires helped him connect with one of his daughters. She would play the game, and she taught him how to use a computer. She was so good at it that she was explaining the basics, possibly the mouse and keyboard for all I knew. She was seven or eight years old and had a complete grasp on how to play the game. My friend said, "My daughter was teaching me more about how to use a computer than I'd had experience with because of your game, and she was having fun playing."

I thought that was another important thing about Age: It crossed all sorts of borders. We were successful in Asia, Europe, America; we were successful with casual gamers, but hardcore gamers were also playing very competitively, and still do. It was a really great product.

BILL FULTON: Age was my first big game I worked on in terms of games we knew would be a success. Flight Simulator paid for all of our failures, and there were many. But Age of Empires was legitimately a good game. In the evenings, there'd be what we called bug bashes, which is everyone playing the game and logging whatever bugs they found in real-time.

RICK GOODMAN: There are two types of players. One is the multiplayer, kill-or-be-killed, zero-sum, competitive player, which is what we all enjoyed. Then there was the single-player who enjoyed the story, turtling, and the experience of building a civilization rather than the experience of conquest. Our game was headed toward the WarCraft/Command & Conquer pattern and I didn't have a way for the game to express big build-ups. I wanted it to be a game that appealed to both audiences, but I didn't know if we could because those are really different games. One of the ways we tried to do that was spending a lot of time on walls.

Walls are important to people who want to build up and keep out other people. That was the best thing we had for those who wanted to build an empire. It wasn't much, but without walls, you can't claim and defend a territory, so I tried to make them extra strong. A lot of people complained about how strong they were at the beginning, and they had to be adjusted for both players because you had to be able to win. There couldn't be a stalemate.

BRUCE SHELLEY: I tell people, "We put a lot of different experiences in that one box." My friends daughter would just build maps: She'd build scenarios and then run around on maps she'd made. Another guy told me his father played through all the missions in Age of Empires, all the way through, and then start over again. He played all the scenarios from start to finish, over and over, and that was very enjoyable for him.

I used to say, "I want the smartest 15-year-old kid in junior high to tell his friends, 'This is the best game I'm playing,' and I want the other kids in that school to go out and play it." Now, they won't be able to compete with that tech wizard, but they'll find a way to enjoy it because there are so many different experiences in that box.

MICHAEL MEDLOCK (senior user researcher, Microsoft): The words usability and playtest are marketing terms. When I say marketing, I don't mean from the discipline of marketing. I mean in the classical sense that they are attempting to explain, in a more palatable way, what these things are to people who don't understand them. Usability methods are what I'd call observational methods at their heart.

Playtesting is about attitude. But a playtest is purpose-built to try and measure an opinion. Opinions are squishy things and hard to measure. To generalize them, a playtest is a survey, and a usability test is, "Have them do a task and observe them."

BILL FULTON: At that point, we were mostly just telling the developers what the problem was and letting them fix it. Later, we would get into more recommendations. But it was simple: People need to be aware of resources and what they're used for; they need to be able to tell what is the resource and what is not a resource by looking at the environment and, ideally, by testing the environment. The cursor changing over a resource became a thing. If you were just moving your mouse around, suddenly it would change. You'd say, 'Why did it change? Oh, hey, why is there a pick over this yellow rock?'

Informational messaging and tutorial-like pieces of information would occur. We would test how well that information got someone to change their behavior in a useful way. Age II's tutorial bar was really lower: Learn how to use a mouse. Age 1's was, take what you already know from WarCraft and apply it to Age of Empires.

RICK GOODMAN: We tried to increase the size of maps. You could choose a small map, but I wanted maps that were really big so people who wanted to could play a longer game and not feel rushed. We had maps with islands so you had to build ships, and it was still hard to cross the water, which gave players more opportunity for empire-building. And we wanted a population count that was as high as possible so you weren't told that after 20 or 40 units, you're done building. We tried to manipulate these factors to make them more palatable to the empire-builder since we favored and were trying to satisfy players who enjoyed the rush.

BRUCE SHELLEY: When we were building Age II, one of our colleagues, Chris Van Doren, kept saying the Vikings were overpowered. He said, "I'm going to play the Vikings every time we play this game until you prove to me they can be beaten." They had the ability to build buildings on the run. You didn't need a villager to build; Vikings could build a barracks wherever they were and pour more soldiers onto the front line. That was one thing that made the Vikings particularly difficult to balance.

Also, archers were thought too powerful for a while. Nothing could close with an archer. A group of archers would kill everything that tried to get to them, so we had to do something about that, make the archers a little weaker. Longbows were pretty devastating in several battles, but ultimately there was an answer for that. People had their favorite strategies, like masses of cavalry.

We learned a lot from Age 1. For Age II, we hired some really good Age 1 players to be testers. We had a crew of those people, all men as far as I can remember. Their job was to play the game every day, break it, figure out strategies that were overwhelming, and identify civilizations that were too strong or too weak. If no one wanted to play as that civilization, we'd have to work with it and figure out a way to get it balanced. That helped us quite a bit. Testing is critical. You need to get a lot of people playing your game.

RICK GOODMAN: Microsoft had a great QA and testing team. They would submit recommendations or observations. I followed up on those religiously because you don't get Microsoft feedback every day. This was my 15 minutes of fame and we would work on the game whether it succeeded or it failed, but I was determined that we wouldn't fail because we didn't listen to Microsoft. Their feedback was really on the mark because we were building a game for us. Nowadays we don't build games for ourselves, but back then, we did. Those three areas--QA, ourselves, and our producer--were great.

I remember it was January 1997, the year we shipped, and we said, "Is this game too simple?" We had this real crisis. Tim came down, and he, Bruce, Tony, and I talked together. We said, "This game is just a simple strategy game. It's not complex. It's not real-time Civilization." We worked through that issue for a month and eventually decided, no, this is a pretty good game. It may not be real-time Civilization, but what we came up with was the direction we wanted to continue in. There's something about your first baby. The other ones, you're like, "Oh, let them cry."

TIM ZNAMENACEK: Obviously I wasn't the game designer; Ensemble had a fantastic design team. I'm not that good of a gamer, so I brought this very beginner-gamer point of view to understanding interfaces: what were my goals, how did I control the characters, et cetera. That's something I'm really proud of and feel I contributed to a lot. I iterated a lot with the on-staff user testing team and the game designers at Ensemble to test the whole game. We tested all the UI. We spent a lot of time on those tutorials.

A game designer [from Ensemble] came up to Microsoft, and we loaded the [latest] build of the game on my machine in my office. That would allow us to edit the tutorial scenarios. Then we would go to user testing, bring somebody in, give them a set of tasks, and watch them go through it. We'd see where people got stuck, go back to my office, iterate on the design before the next person came in. We iterated and iterated. It was a little excessive, but we had middle-aged and older people who didn't play games at all, and who were very light computer users.

RICK GOODMAN: It was months before release that we came across something that I thought was a breakthrough. Tim Deen came into the debrief room and said, "What if you build a moment, and it starts a timer? If the building is still standing when it expires, you win." That proposal was to address a recurring question we had, which was, "How does an empire-builder play this game?" Because you have to kill everybody to win, and that wouldn't be true to a civilization game.

During the debrief, Tim left the room. He came back 15 minutes later and said, "You guys still arguing about this? Because I just programmed it." We tried it and it was an instant hit. People tried it and were like, "This is so cool." We would all try to take time and gather resources to build this monument and protect it to see what would happen. There was no game that could show us that pattern. After adjusting the timer from five minutes to 15 minutes, and adjusting walls and towers, and putting the monument at the right place in the tech tree, it was pretty well-balanced for both conquerors and empire builders. My guess, and I'll never know, is that one significant change made the game so much more widely accessible in a game that had just been about killing people. I would guess it doubled or tripled sales of the game, because people could play whatever way they wanted to play.

TIM ZNAMENACEK: I was having this debate with the designers at Ensemble's about when you select a villager to queue them up to build, do you take the resources out of the resource inventory as they're added to the queue, or as they're being built? We did an A/B test with user testing, and A/B testing wasn't really a thing yet, but that's what it was in retrospect. I think I won, but I don't remember which side I was on. The customer won, really. What I cared about was whether it was intuitive for the customer, the gamer.

RICK GOODMAN: One of my favorite experiences is when someone else ruins your plan. In your mind, you'll say, I'm going to defend. Then you're suddenly forced to attack. You think, What do I do now? It's a big mental shift. What I didn't anticipate during playtesting was, what happens when everybody's building monuments? That was just a bizarre, fun free-for-all that could go on a long time. You had six to eight clocks running at different times. I didn't realize what a Pandora's box that would be, but I think we thought that was even better than just a clock. It's like, "I've got to be over here. Then I've got to go over there, and I've got to defend my monument."

It was super-lucky that we kept pushing to try to find a solution to this problem I thought I'd given up on that ended up taking Tim 15 minutes to program. It showed that sometimes the hardest problems to solve are the creative ones. It's not about technology. It's about asking, "Can I get my brain to figure out this idea?"

STUART MOULDER: One of our challenges was that the game's AI was not strong when we shipped. We all played Age a lot. You quickly figured out who was good and who was bad, and I was not one of our better players. I loved building, so I'd tend to put too much into buildings and research, and not enough into raids and early combat. You had an AI for the single-player game, but most people weren't interested. They loved the competition of multiplayer. I was one of the people who liked single-player, maybe because I wasn't good at multiplayer, I don't know. As we neared the finish line, I beat the AI on all levels of its difficulty up to its maximum level, where it cheated, so I ignored that. But on the highest difficulty below that one, I could handle it.

I went to our AI tester, a guy named Mark Thomas, and said, "Hey, I've got to tell you that I win every single time without breaking a sweat, and you know I'm not very good." Mark was one of the people who liked to make fun of me, because again, I wasn't very good, and he said, "Oh, yeah, you suck," or some comment equally professional. I would get him my save-games and he'd send them off to David Pottinger, who was the AI programmer at Ensemble. David would go in and tweak some things and send back a build. In the last few weeks, I became our AI tester, basically. I'd go home with a new build, play every night, come back with save-games, and report.

At one point, Mark finally said, "Let me watch how you play." My thing was I'd build a wall around a big chunk of territory and just go blast through the Ages, build a Wonder, and win, because the AI wasn't good at getting through wall structures. Human players had no problem with it, but the AI just didn't know what to do. Mark looked at what I did, he looked at me, and he said, "Well, you're playing in exactly the way that exploits the AI's weaknesses." And I just looked at him, and he said, "Yeah... I guess that's what people do, isn't it?" I'm like, "Pretty much."

They kind of sighed because it was a hard problem to solve, but they did it. About a week and a half before our ship date, they gave me a build, and I went home and got beat playing my strategy. The idea wasn't that I should never win on the second-hardest difficulty, but that it should feel hard.

BILL FULTON: Because it was so multiplayer-focused, you had to have lots of people playing games to see what bugs would arise during play. We'd do a conference call with our team, and their team would have a conference call.

I remember walking down the hall one night--there were a couple hundred people at that point--and all you could hear was the sounds of combat and people yelling that they needed wood, and someone saying there were five archers invading them from the south. I thought, Okay. This is home.

Part 6: Conquest

Just when Age of Empires seemed ready to step onto the strategy genre's crowded battlefield, the combined team of Microsoft and Ensemble arrived at the conclusion that the game needed a few more turns.

STUART MOULDER: As the game developed, it became better and better. We very quickly identified that as maybe our first potential, breakout "gamer" game from Microsoft. A couple of key things that were super-important were the game was from a new developer and Microsoft was a newer publisher. We had hoped to publish the game after a year and a half or two years of development, in '96. As we got closer to that, we realized that while the game was working and was good--you could build and fight; we had multiplayer; we had basic technology trees--it was pretty rough. The feeling was if we could take another six months at least, we could turn something solid but forgettable into something great.

We went to Ed Fries and told him that, and he was 100 percent behind that. He didn't want a "B" game. He wanted an "A" or "A+" game. Part of Age's success has to be credited to Ed, who took heat for delaying, ultimately by a year, a game that we'd gotten our marketing people pretty excited about.

ED FRIES: I don't remember that at all. What I remember is there was a lot of turmoil. I had taken over this job and then three months later, my boss, Charlotte Guyman, quit. And three months after that, her boss quit. I was kind of unsupervised. At that point, I reported to a senior vice president, which didn't make any sense given what my rank was at the company. I was kind of on my own for a while. Maybe I played it up with Stuart that it was a bigger deal than it was. [laughs] I honestly don't know. But it sounds like I did the right thing, so that's good.

TIM ZNAMENACEK: I don’t remember it slipping a full year, but it did slip significantly. At least six months, but my recollection is not that strong on the duration. People on the team just knew this game was going to be a commercial success during development due to how addicted everyone was. Ed saw that level of potential as well and gave us the time and funds to really give it the polish time it needed.

STUART MOULDER: At Microsoft, you didn't do what we did with Age, delay it, with Word or Excel. Those products came out when they were supposed to come out. Maybe they were buggy or lacked some features, but they came out on a set schedule because in the business world, you had partners lined up, from OEMs to IT managers, all with an expectation that the new business software will be out at this time. You didn't change those dates.

The idea that we would take something the marketing people were ready to roll with and push it out to another holiday was a pretty hard thing for people to swallow at Microsoft. Ed took quite a bit of heat for that one. To be fair, it wasn't like people couldn't understand that a good game would perform less well than a really good game. But it was difficult culturally for Microsoft to accept that.

Another part of it was that Microsoft is a business company, and they'd had their fair share of delays. They had worked very hard over the preceding decade to really fix their systems and processes so that didn't happen. There was a little bit of a feeling of, "You guys are turning back the clock and forgetting all the hard lessons we learned on how to ship things on time." It was hard for them to understand that a game has different criteria for being ready to go out the door. But Ed fought that fight and won.

ED FRIES: I know what Stuart told you, but it's not exactly right. On Excel, we developed--and when I say "we," I should credit my boss, Chris Peters; he was the driving force behind this--he wanted to develop a system where we could have a strong schedule that we followed and shipped on time, but in a way that didn't destroy the lives of the people on the teams. First of all, it involved convincing the programmers this was in their best interest. It was like a shield. When the program managers, who were kind of the designers on the Excel side, woke up in the morning with a great new idea, they would come to us and we could say, "Here's all the other stuff you guys want me to do. If you want to slot this in and change the priority, go ahead and take out an equivalent amount of something else." That worked well.

Word and some other Microsoft products--Windows, most famously--had a reputation for slipping. We would meet with Bill and we'd be mad because when we shipped the first version of Excel for Windows, we were tied to Windows 2.0, and Windows 2.0 kept slipping and slipping to the point that it slipped past our ship date. We required Windows 2.0, so we made them give us a special version of Windows that we could ship with. When that first version of Excel for Windows came out, you've got to remember that a lot of people didn't have Windows yet, but we actually had a runtime version of Windows. Excel would effectively boot Windows and launch Excel. When Windows 2.0 finally shipped a few months later, you could just stay in Windows and run Excel.

But we would complain to Bill: "Why do you let Windows slip? We're on time." And he'd be like, "Oh, you guys don't understand. Windows is way harder than what you do," which we didn't believe. On the Office team, we were proud of our history of having a system to keep us on schedule.

Chris and I both went over to Word and took over after Word 2.0. We brought that same philosophy and got Word on a similar schedule. Then Word and Excel merged to become Office, and people who grew up under Chris's system, like me, went on and took over the Windows group. After Windows 7 was a disaster, they did Windows 8 and Windows 10--which were also disasters, but at least they were on-time disasters. [laughs] So it's true that I had a lot of that training when I came to the games group, and I tried to apply it where I could, but it wasn't always applicable to an entertainment product.

RICK GOODMAN: Tony [Goodman] didn't care about shipping anything that wasn't the highest quality. We figured that if this was going to be the only game we shipped in our lives, we were going to be proud of it. Never did we cut corners on quality. Another lesson was collaboration. That means playtesting a lot because you just don't know what you have, and playtesting is a beacon to follow. You may not know what you're doing, but every day, you're going to make progress, probably in the right direction. Super-inefficiently if you don't have a visionary, but if you have a visionary you don't have confidence in, playtesting is another way to approach the problem.

Everybody playtested every day. We did debriefs every day. We had a list of things to do or fix that was so long. But we would address every one eventually. Month after month, we'd see improvement. Related to that was time. You can't have collaboration without taking the time needed for that. Time, collaboration, and quality.

With the end finally in sight, Microsoft and Ensemble's developers, testers, and producers worked even harder to hit a level of quality that would raise Age of Empires above the other RTS titles vying for attention.

BRUCE SHELLEY: I used to travel for MicroProse and Ensemble on behalf of those companies and our games, so I've met a lot of journalists. I've had to speak at conferences. One thing that's stuck with me is in the early half of the game you're making, it's like playing soccer: You're actually trying to score goals. You're trying to kick the ball into the net with great concepts for things players can do. It's fun. You're really scoring, scoring, scoring. Hopefully.

RICK GOODMAN: The last three months for me were 12-hour days, seven days a week. I was producer and designer, and I didn't have time to do design during the day. I had to do it at night, and I was pretty tired. We had a problem with out-of-sync bugs. We were like, "This is so hard to solve." We'd never made a game before so we had no tools for this. We just didn't know what to do. I was very concerned that the out-of-sync rate in a game with eight players, when there was a ton of stuff going on, would be statistically too high to ship. I said, "I don't know what the statistic is, but I'm worried about it. We don't have enough time to play 100 games and get those statistics to find out if this concern is valid or not. But what if we played 100 multiplayer games where there were no human players involved?"

That wouldn't take a lot of effort. We rigged up a game that had a human that couldn't be defeated, and seven opponents. That required that somebody connect eight computers and run full games through 100 times. This couldn't happen during the day, so I volunteered to do it after everybody left. I would start that shift around seven or eight o'clock, and I would run as many games on these 16 computers as I could. Then I'd go home and sleep when everybody came back to work. I got to a hundred games after two weeks. I told the guys the good news: Only two of them fell out of sync. We felt so much better. It wasn't a perfect test, but it was good enough for us to feel comfortable that it wasn't as broken as we had feared. We loved our game and thought it would do well, but nobody had any idea what was going to happen.

BRUCE SHELLEY: When you're about halfway through the game and you've got enough to make a quality product, you switch to goalie. You're defending this concept, your design, from other ideas that people want to bring up. If you don't defend the goal, the game could go on forever.

We had mission creep at Ensemble. Microsoft was willing to let us work on things, especially when they came up with things they wanted us to add. Our games drifted a little long in most cases, and Blizzard's games seem to take a long time. That was my thought: Score early and defend later.

Microsoft had published games before, but Age of Empires was different. It wasn't a DOS game given a slight graphical touch-up for Windows 95, or a title of more interest to amateur and professional pilots than it was gamers. It marked Ensemble's first release and first success, and, in a way, the first triumph of Microsoft's games team, perpetually fighting for legitimacy within the behemoth organization.

TIM ZNAMENACEK: There were bigger Microsoft games before Age, like Fury3, the 3D space shooter. Before Age of Empires, I worked on a game called Deadly Tide, which was more of an interactive video game. Beautiful game and cool, but not a very fun game. I think we were at release or just about to release Age of Empires 1, and Stuart Moulder was leading the group that owned Age of Empires. He sat the team down and said, "You guys, I'm telling you: Shipping this game will be the highlight of your careers. This is the biggest thing that's going to happen to you guys." We hadn't even had one sale yet, but he knew.

STUART MOULDER: I did that in one of my staff meetings where I said, "This is it." I tried to emphasize to people, "You'll remember this for the rest of your life. You'll remember that you worked on this game, and whatever else we do, this will be one of your career highlights and one of the things you'll be proudest of." I'd been in the industry just long enough, had seen enough products go out the door, that I could look at this and say, "Yeah." The Windows 95 team probably had that feeling.

I was a history major in college, so I had sort of this historical narrative in my head of what's going on and how it will feel in the future when I look back. I remember feeling like, "Yes, I've shipped a lot of games by this point, and I've got to tell you guys, you should really embrace this, because it's going to be one of the things you look back on and are proud of." I think the original Xbox team--hardware, software, all sides--probably had the same feeling. Like, "I've gone through Hell, but we've launched something I'm proud to be a part of."

RICK GOODMAN: I remember right around release, maybe a week before or after, reviews started coming in. That's pretty nerve-wracking. You couldn't talk to your customers. You could only read reviews. The first review I read was GameSpot's, and it was a 6.8 out of 10. We were really disappointed. That hurt a lot. I thought, I guess all that work was for nothing. I wish that hadn't been the first one, but it taught me to have a thick skin. If you read bad reviews, you'll be depressed and you'll think the game sucks. Today you can look at your dashboard and say, "Oh, actually, we're really successful." A week or two later, there were five, six, eight reviews, and I was like, "Thank god."

ED FRIES: When we shipped the first Age of Empires, that was really when we started to get recognized as, hey, maybe this company can actually make games that hardcore players want to play.

BRUCE SHELLEY: We had a good working relationship. One of the guys up there who no longer works there, he said to us, "They ought to be happy. You've funded their game development for years." The Age series made so much money. They bet on several studios and invested in several games. I remember presenting at a conference they held for journalists, and ours was one of several different games in the presentation. Ours was the one that made the most money by far. We understood we'd made them legitimate publishers in the games industry.

STUART MOULDER: The thing about Age historically for Microsoft and its push into the gaming world was we had a game that got not great but good reviews. Critics dinged us for the AI and some of the stability issues around multiplayer. We took hits also, in part, because we were Microsoft. It was like, "Why are you guys even doing this?" There were internal issues with that, too. People within Microsoft were upset because we were doing games that involved warfare and shooting and so on. Microsoft employees tend to be a little progressive, and they weren't fans of Microsoft peddling entertainment that seemed to glorify war and combat. We got through that, but there was definitely skepticism. We had to push through editorial skepticism [from press] that a normal game publisher would not have had to get through.