SPOILER WARNING: Icon of Sin goes into detail on the making of Sigil, John Romero’s expansion for the original Doom. As such, there are light spoilers on specifics such as elements of level design and boss fights.

JOHN ROMERO STOOD with one foot in the past and one in the future.

He was building Doom levels again, back in his element after more than two decades away. The experience was at once familiar and fresh. He had not made any of the hell-themed maps from Doom’s original three-episode campaign, sticking to bases for Episode 1. His new bundle of maps, called a megawad, would enable him to leave military bases and futuristic labs and descend into rivers of lava, fiery floors, and deep, dark caverns.

But this was 2017, not 1993. His tenure at id Software had ended 21 years earlier. He no longer lived in Texas, where he’d spent nearly every waking hour of his id years with John Carmack, American McGee, Sandy Petersen, and the rest of his former cohort, most of whom had left the studio to pursue other ventures. Romero and his wife, game developer Brenda Brathwaite-Romero, had moved their family and company, Romero Games, from the United States to Galway, Ireland, for a fresh start.

Crafting memorable Doom maps was no longer Romero’s full-time job. It was one plate spinning among many. Fortunately, making his E1M8b and E1M4b maps had proven to Doom fans, and most importantly to Romero himself, that he hadn’t lost a step. Around December 2017, Romero began to think seriously about the types of levels he wanted to make, and how to fit them into his schedule. He would design maps part-time, squeezing in a few hours on nights and weekends around paid speaking engagements and his work at Romero Games.

As for a theme, Doom itself delivered one on a bloody silver platter. December of 2018 would mark the 25th anniversary of the game’s release. What better way to ring in the occasion than by designing a fifth episode?

Romero wanted his megawad to feel like more than just a pack of maps. He knew the game’s code, so he could do things like make his episode appear in the main menu underneath Knee-Deep in the Dead, The Shores of Hell, Inferno, and Thy Flesh Consumed, cementing it to players as the game’s fifth and final chapter. He also knew the new episode’s difficulty should assume continuity: Players had had decades to master Doom’s toughest levels, most found in Episode 4. That was the bar, and Romero set out to raise it.

“I wanted to make sure the pressure was always on,” he said. “My design choice was, ‘I need it to be really hard for me to finish a level.’ That meant it had to be really tough.”

Romero brainstormed ways to have his episode extend naturally from Thy Flesh Consumed. Episode 4 culminates in a battle against the half-mech, half-abomination Spider-Mastermind. After players put it down, they step through a portal and read an ending that reveals the demons have invaded earth, leading nicely into Doom 2.

Romero came up with a neat segue from Episode 4 to Episode 5. Throughout the game, players come across giant murals depicting a goat-headed deity known as Baphomet: part horned demon, part goat, part humanoid, and, according to lore Romero wrote for his megawad, all mastermind.

“I changed it so Baphomet had put a sigil of power inside the final teleporter that was supposed to send you to earth, but it glitched the teleporter and redirected you to an even worse location in hell,” he explained, referring to the last few moments of Episode 4: Thy Flesh Consumed. “Now you have to burn your way through this part of hell to defy the sigil and get to earth, and annihilate all the demons that have invaded in Doom 2.”

Romero named his episode Sigil, a nod to the artifact in his story. “I liked the idea of keeping it with the way Doom is just one word.”

Moreover, he owns the Sigil trademark, giving him space to expand the property in the future. “I could do Sigil: Something. We'll be using the word Sigil for more than this project.”

The setting of Sigil, a far-flung corner of hell, promises to push difficulty to its limits, as well as play up Doom’s more controversial elements. “When I think about it, the satanic imagery in Doom was kind of light,” explained Romero. “I could push that imagery a little bit further.”

Most of Doom’s iconography was less sacrilegious than it was grisly: dismembered corpses twisting on chains, bloody hearts beating atop altars, walls painted in blood and monster guts. To Romero’s thinking, laying on a thick layer of satanic imagery—more pentagrams, more demons, more Baphomet—would drive home his story that players were trapped in one of hell’s worst neighborhoods.

To convey an appropriate level of threat, Romero needed the perfect key art. Doom’s key art is legendary: The eponymous Doomguy in hell, framed against a backdrop of hot and hazy reds, oranges, and yellows, desperately—and resolutely—firing a gun into a pack of demons trying to drag him into a pit. The scene, plastered across Doom’s box and on the covers of gaming magazines, was so impactful that id recreated it for the release of “Doom 2016.”

Brenda Romero found just the right artwork. She came across a painting of Baphomet by Christopher Lovell, an artist based in the UK who specializes in horror and designs for metal bands like Misfits and Bring Me the Horizons. Lovell’s depiction of Baphomet is haunting. Done in whites, grays, blacks, and browns, it portrays the deity’s goat head with long, curved horns, and red eyes, all surrounded by skulls and clawed hands. The detail of the painting is beautiful and intricate, in a heavy-metal-meets-hell sort of way. “When I saw it, it was insane, just amazing,” Romero said. “But when we saw a mock-up on boxes, I was like, ‘That's the coolest box I've ever seen. I have to have that. That has to be on Sigil.’”

Romero secured Lovell’s image for Sigil’s key art, with an extra touch. Denman Rooke, lead artist at Romero Games, fashioned a Sigil logo that contorted the title’s lowercase “g” into a twisted 666, the mark of the beast. Rooke planted his Sigil logo in the center of Baphomet’s forehead.

“He put it together, and I said, ‘Unbelievable. That is the perfect logo. How has that not happened already?’” Romero remembered. “I have the domain si6il.com for Sigil, and that redirects you into the press announcement until I have a page of cool stuff ready.”

EVERY ROOM IN Doom can be broken down into smaller pieces: rooms made of textures on segments shaped into lines, all stitched into a morbidly colorful world. Romero can whip up a room in seconds, but even the game’s co-creators have their limits.

Those limits are set by Doom’s engine. Floors, ceilings, height, even textures—a level can hold only so many of each, and those maximums are defined set in code. The most infamous limitation is a map’s maximum number of line segments. Romero toyed with the idea of workarounds, such as candles placed upon an invisible staircase to make the candles look like they were floating. Ultimately, he decided against fancy tricks.

“I asked, ‘What can I do in a design space, rather than tech-tweaky garbage?’ which really isn't where design is. Design is in, ‘What can you come up with visually and mechanically for this space?’ I wanted to stay in that realm.”

The first level Romero made for Sigil was E5M7. It was originally going to be the episode’s fifth map before he decided its massive size warranted placement closer to the end of the campaign. The first room he designed for the map was not the room where players started. Approximately midway through E5M7, players teleport into a chamber where a body dangles in front of them. When they turn, a door opens, and zombified shotgunners open fire. If players try to put some distance between themselves and the gunners by moving toward the hanging corpse, they’ll fall into a pit of lava and have to scramble to find a way out.

E5M7—like most of Sigil’s maps—tests players’ ability to keep their cool as much as it gives their trigger finger a workout. “What I wanted to do was make a room that would be difficult to get out of, and got worse as you moved around in the room. It was almost like, ‘Don't move around too much! You're going to die!’”

The room’s layout adds to its challenge. Floors curve, and Baphomet’s demonic mug scowls at them from several angles. Players must escape the lava quickly, but they’ll often rush from the proverbial frying pan into the fire. “For me, it was really different because it's very curvy, lots of curves in that room,” said Romero. “It's got a broken wall you can get through, but there's a Cacodemons shooting in at you. The walls open up behind you and here come two more Cacodemons and a shotgunner. It's so hard.”

E5M7 came together in fits and starts, the way Romero has designed all of his maps for Doom and Quake. To get a feel for a map’s flow and challenge, he jumps from the editor and into the game every time he adds anything: an enemy, a weapon, an ammo pack, even a texture.

Of all Sigil’s maps, Romero may have iterated on level 7 the most. The fact that it was his first meant he was practically guaranteed to devise more efficient ways of doing things later on, and them coming back to bring earlier maps up to snuff. “When the level's done, I have [accumulated] maybe a thousand plays of the level, because I run it every minute or so that I'm working on it to make sure everything looks good, that I don't have any errors. That's the way I code as well: code a bit, test; code a bit, test. I don't code for half an hour before testing. I've got to see it, got to feel it, got to play it.”

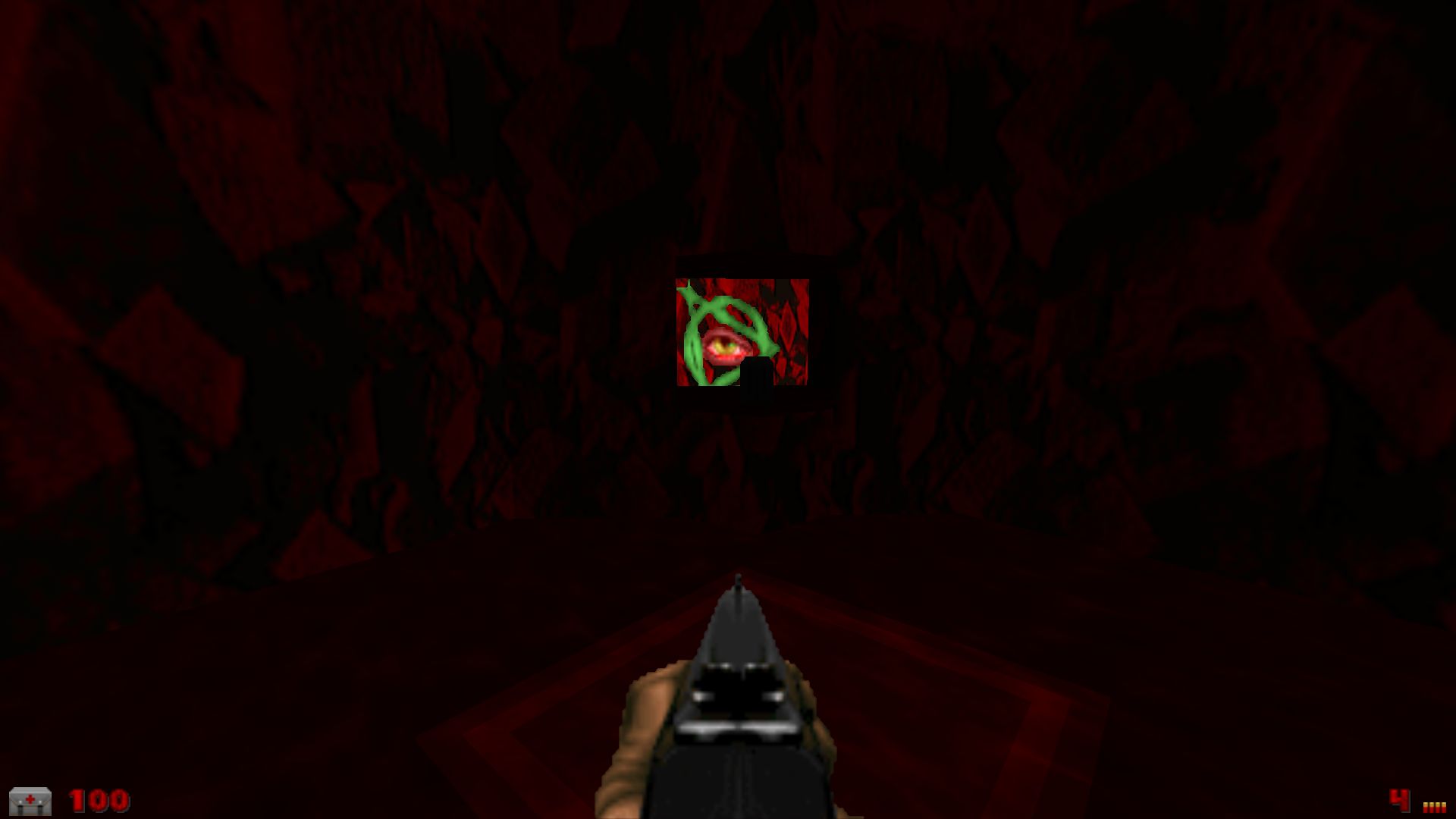

In another part of level 7, players are ambushed by Cacodemons that can rise out of a pit in the center of a building. Romero ended up revising that area several times because he forgot to add one important property: Shooting an Illuminati eye to open or close a wall in the room, so that players may leave and re-enter at will. The room’s final design is a nest of line segments connected to architecture, trigger events, or both.

The Illuminati eye is a centerpiece of Sigil. It appeared only a few times in the original Doom, and served as mere set dressing. In Sigil, it’s combined with another little-used building block of Doom’s level design: The ability to open a secret wall by shooting it. “I only used it once, the line segment where you shoot a wall and it does something,” Romero admitted of the original game.

Romero’s single usage can be found in Doom’s E1M2. First, players must press a button that opens a wall to admit them into a secret warren of dimly lit computer terminals. Near the back of a particular hallway, players can shoot a wall to reveal a narrow passage that leads to the chainsaw. The problem with this instance was that players were given no indication that shooting the wall opened up a new path: The wall looked like any other wall. Most players stumbled into the secret-within-a-secret by shooting at the Imps lurking nearby and hitting the wall instead of the monsters. Also problematic was that most players would never think to waste a bullet by shooting what appears to be an ordinary wall, especially if they’re new to the game and hard up for ammunition.

Romero uses the shoot-to-make-things-happen trigger more often in Sigil, and more purposefully. The first room of E5M1 is a star-shaped cavern covered in blood. There is no switch, lever, button, or door. Instead, players find their attention diverted to a niche in the wall. Through it, they see an Illuminati eye. A box of bullets sits in front of the eye. “You pick up the ammo, and maybe you'll think, Oh, I guess the ammo is for this. You switch to a gun, and shoot the eye,” Romero said.

Shooting the eye lowers a nearby wall, revealing the way forward. Along the path, players must search for another eye. Shoot it, and a bridge rises. They advance, and come to another dead-end. By now, they should know what to do. “On level 1, the only way to progress is to do this five times,” said Romero. “You can't finish level 1 if you don't shoot five of these things. Level 1 is teaching the player about these evil eyes: That they help you progress, and help you find secrets.”

Using eyes as switches has the added bonus of fulfilling weapon balance. In designing the original Doom, id’s team wanted each weapon to serve a purpose. Just because players get their hands on a rocket launcher doesn’t mean their chaingun or shotgun should be left to collect dust. In Sigil, players will learn to switch to their pistol and fire a single bullet into eye-triggers, rather than waste a shotgun shell or—since it fires faster—two rounds from their chaingun.

“You have to switch to a gun that uses bullets, so I have to make sure players have ammo before they get to that point,” Romero said of choosing when and where to place the eyes. “I have a progression list of which levels should get a weapon, and which should hide a weapon in a secret. All the basic balancing you'd do in any game, I've made sure to do in Sigil.”

PLACING SECRET AREAS was and still is a point of pride for Romero. Doom and Quake hold up today not only because their straightforward, shoot-everything-that-moves pedigree makes them welcoming, but because their environments are fun to explore, especially when nosing around a level is rewarded by way of secret areas and caches of supplies.

Sigil’s E5M1 holds a secret Romero claims is his most devious yet: A triple-nested series of hidden areas. “Level 1 has an area that is probably as big as the whole playable space that you can see only from the first secret area,” he said.

The space, a massive field, holds five pentagrams, symbolizing each of Doom’s episodes. Once in the second secret area, players are bombarded with details: decorations, paths, and, observable only to a keen eye, a sliver of blue pixels—a Soulsphere, the glowing blue head that boosts players’ life points by 100.

In a way, the act of uncovering E5M1’s nest of hidden areas is more satisfying than looting those areas. Catching a glimpse of a room or item they can’t reach incentivizes players to explore rather than rush through a map. Journey over destination. “It's kind of like an escape room,” Romero said. “When you get in there, now there's another weird puzzle. If you look really closely, you'll find another secret. That's the third secret, but you can just barely see it. I do this stuff all over the place: I want to give the player just a hint of something so they'll go and figure it out.”

Doom was as memorable for its tense, scary atmosphere as for its fast pace and expansive levels. Sigil follows its example. Every level oozes atmosphere as players run, fight, and explore. Areas of level 2 are tight, almost oppressive; in other regions of the level, players must backtrack through dark rooms and corridors to advance. Level 3 reveals itself in layers, a nod to Romero’s E1M4b. Level 5 is peppered with what Romero calls hell lightning, red lightning that flashes and ripples along the sky. “It's just strange, and the music is really weird, which plays into the mystery of, what is that stuff? I only did that on that one level.”

Of all the rooms and stages in Sigil, Level 6 hosts Romero’s favorite: A maze straight out of Greek mythology, with a Cyberdemon standing in for the Minotaur. Enemies walk paths atop the maze, shooting and throwing fire as players navigate. A soaring tower holds a Baron of Hell, like a prison guard monitoring the grounds. But the most stressful part of the maze may be the fact that players can hear the Cyberdemon stomping around as they search for a way out. That ominous stomp is terrifying on multiple levels: it’s a sound that makes even the heartiest of Doom players quake; and it communicates that the monster isn’t content to sit and wait for players to come to it.

Designing that maze, as well as the rest of Level 6, stretched the limits of Doom’s engine. Before players reach the labyrinth, they come to a dark area near a river of blood. Three Barons of Hell teleport in to force players to fight or flee, but one wrong step could find them standing on a platform that drops them into the corrosive blood.

Those lifts, deceptively simple in appearance, are wired with numerous vertices and line segments that give them their curvy shape. Early on, all those segments clashed with the player-character’s rectangle, the hit box around the model, in a way Romero hadn’t encountered before. “Doom can't process more than eight line segments being intersected by the player's hit rectangle. It's this super-technical thing that almost nobody has to deal with, but I'm getting feedback saying, ‘It looks like you hit this crazy internal limit.’ I had to simplify the shapes to make sure that wasn't happening.”

Following tradition, E5M8 is Sigil’s final level, with E5M9 stashed away somewhere for players to unearth. Level 8 is perhaps the most nerve-wracking of the campaign. It starts small, with players spawning behind a wrought-iron fence. The environment is dimly lit, though players can see bonfires along the room’s perimeter. The action picks up as players explore. Lost Souls teleport through the fence to harass them, and sibilant hisses announce Cacodemons drifting somewhere in the darkness.

“That level doesn't let you just sit there,” Romero said, laughing. “I'm going to do a little modification [before release], just to make it harder.”

Visibility can be considered a theme of E5M8. Players rarely see all the environment holds in store for them by standing at one vantage point. As soon as players reach the other side of the fence, they’re running from Imps, zombies, and Cacodemons, racing across rocky ground that pulses with glowing fissures. Like Illuminati eyes, the fissures hold clues: One’s zigzagging trail ends at the foot of a building, subtly directing players to go inside.

The final minutes of the level are as memorable as any eighth mission of Doom’s original campaign. Players enter an outdoor environment with high walls on either side, and a Spider-Mastermind far in front of them. Like other parts of E5M8, the encounter seems straightforward: kill the demon, move on.

Then players round the corner and wake up a Cyberdemon lying in wait. It marches forward firing volleys of rockets as it closes in. Players’ instinct may be to run back around the corner and regroup, but the Cyberdemon acts like a wall that inexorably moves forward, slowly but surely shrinking the gap.

Sigil feels like a natural extension of The Ultimate Doom, and can be played with contemporary bells and whistles such as vertical aiming, and jumping and crouching. But Romero cautioned that using those features, unavailable in 1993, would take some of the fun out of Sigil’s most challenging fights and intricate maps.

“It's been really fun,” he said. “I love making Doom levels, and it's been fun to push forward. This is stuff I could have done in the last 25 years, but I did other things, and I thought this was a great time to do it.”